Concept work on the recently opened exhibition, Design for Life, started in late 2019. At this point in time, Australia had not yet experienced some of the worst bushfires on record and the world was blissfully unaware of the pandemic that would emerge in early 2020. Who could have guessed that our decision to include a selection of masks from our collection would become so relevant to our lived experiences at the time of opening.

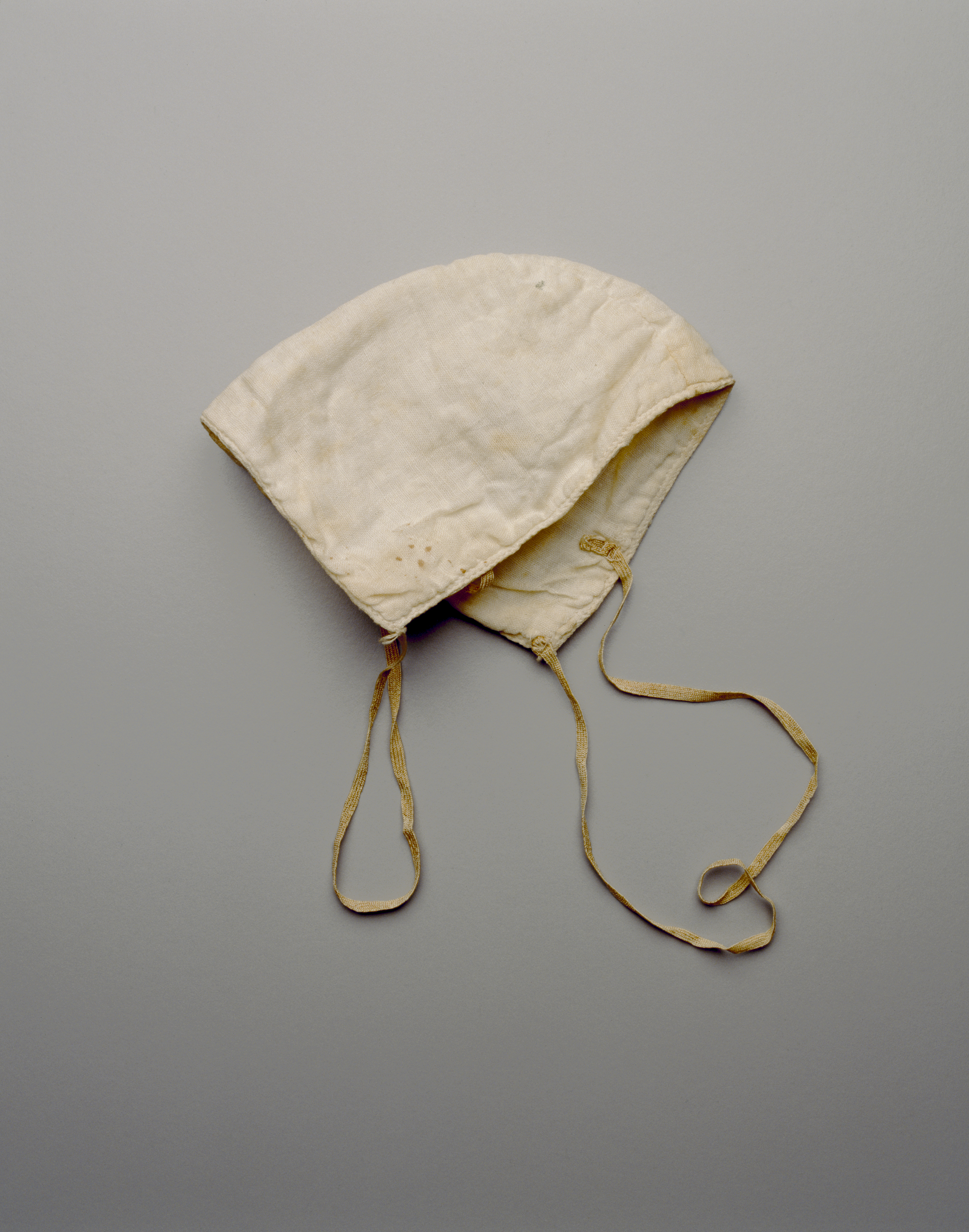

The Museum’s collection contains masks dating back to the early 1900s. This cotton face mask with its rounded shape and earloops is remarkably like those many of us are wearing now. Purchased by the museum in 1990, it has been dated to around 1917 and this design could have been used by health care workers and volunteers during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1919.

The use of masks in times of plague and disease is not new. In 1861 Louis Pasteur proved the presence of bacteria in the air and in 1897 Carl Fluegge showed that speaking could spread infection. It was soon recognised that a multi-layer gauze mask, like the one above, was successful in protecting the wearer against infection and important for maintaining sterile conditions.

Surgical masks however are only one part of the story. This World War II anti-gas respirator set was not developed to combat disease. It was developed in response to the threat of chemical warfare. Unlike a surgical mask, respirators are designed to create an airtight seal on the face, so that air is inhaled through the filter and not the sides of the mask. This model also had unique design features that directed the incoming air over the eyepieces, preventing condensation, and sealing the clean air in the tube during exhalation.

The company, 3M (Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing) was first established in 1902, in Minnesota, USA. But it was in the late 1950s that Sarah Turnbull suggested 3M invest in non-woven products. This ultimately led to their first single-use N95 ‘dust’ respirator in 1972, with non-woven material serving as the mask’s main fabric and filter. Initially adopted for industrial applications they only entered clinical settings after we experienced modern epidemics of airborne diseases, such as drug-resistant tuberculosis, avian flu, swine flu, and SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome).

There are many challenges with current N95 masks, they won’t seal well on people with facial hair or children, and they become extremely hot and increasingly difficult to breathe through. Despite this, they will become essential tools in facing future challenges such as new diseases and increasing pollution.