In this guest report Toner Stevenson, History Affiliate at the School of Humanities of The University of Sydney, celebrates a significant centenary…

On 21 September 1922, Australians and local and visiting scientists gathered in prime locations to observe the Moon completely cover the Sun. Astronomers around the world had been anticipating this eclipse because it was the opportunity to confirm, beyond doubt, Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. A total solar eclipse occurs when the Moon completely covers the Sun as seen from the Earth. You can find out more about eclipses here.

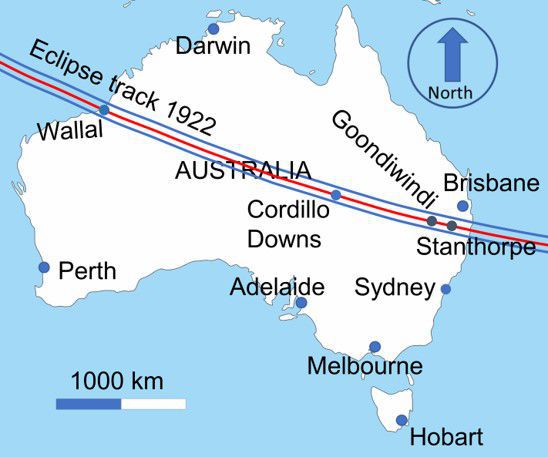

This total solar eclipse swept from coast to coast across Australia with a long period of totality of 5 minutes 18 seconds on the west coast of Western Australia. The duration of totality reduced as the shadow of the Moon crossed the continent to south-eastern Queensland. This eclipse was well documented, and there are many photographs in the Powerhouse collection of Sydney Observatory’s eclipse expedition to Goondiwindi and many other expeditions.

Fig 1: Map of the 21 September, 1922, total solar eclipse path across Australia. Toner Stevenson.

This eclipse had several advantages over four previous eclipses, the most recent of which was in 1919, at which attempts to prove Einstein’s theory had been made but with varied success. Not all astronomers were convinced and William Campbell from Lick Observatory in California was doubtful that the results produced by British astronomers were sufficient evidence. William Campbell and his wife Elizabeth Campbell organised a substantial expedition of men and women to a remote area of Western Australia called Wallal Downs where totality would be longest. He had new equipment especially designed to take photographs of the stars surrounding the eclipsed Sun and support from many organisations including the Royal Australian Navy.

The press and scientists made a great effort to ensure everyone possible, including school children, had information about the eclipse and how best to safely observe it. A booklet produced in the months prior to the eclipse by Henry Ambrose Hunt, Director of the Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology, described the best viewing locations, time adjustments for the eclipse partial phases, length of totality and predicted climate in many towns across Australia. It featured opinions by astronomers and described which official parties were travelling where and what their objectives were, detailing their equipment and plans. This was a ready guide, which a first-time eclipse viewer could follow, and had several warnings about eye damage and how to avoid this as well as instructions on how to sketch the corona.

There were many expeditions to locations along the path of totality. Wallal Downs was a pastoral station in a remote area of the coast of Western Australia, to where scientists from the United States, Canada, India, New Zealand and Western Australia travelled by rail and sea, determined to contribute to the scientific endeavours; astronomers from Adelaide Observatory went outback via camel and motor car to a remote sheep station called Cordillo Downs; Sydney and Melbourne Observatory astronomers, who packed aging equipment and travelled by train to the racetrack at Goondiwindi in southern Queensland; a small group of keen observers, who fitted out their motorcar and headed north (you can read more about amateur astronomer, Miriam Chisholm, and her expedition here.) and, finally, we will join seasoned amateur astronomers from the NSW branch of the British Astronomical Association in Stanthorpe, who found high points from which to observe the Sun as it sank towards the western horizon.

The details of the eclipse expeditions were well-documented by the astronomers and the press. In the end all the expeditions had some measure of success in photographing the eclipse. The Lick Observatory group were successful in confirming Einstein’s theory. On every photographic plate the stars nearest the Sun were shown to have been displaced. 84 stars unequivocally displayed a displacement acceptably close to the amount predicted by Einstein. Campbell noted that this was likely the first time such faint stars very near the Sun were able to be photographed during an eclipse and, in his and his assistant’s report of June 1923, they announced that the experiment was a success.

Fig 3: An ‘Einstein plate’ showing the Sun totally eclipsed. Lick Observatory Photographs UA36 Ser.7/ Special Collections and Archives, University Library, UC Santa Cruz.

What was also extraordinary about this expedition was the involvement of many women in the scientific work and the local knowledge of First Nations People at the Wallal Downs eclipse site. Through the lens of the film maker Ernest ‘Bud’ Brandon-Cremer, reports of the eclipse and Elizabeth Campbell’s diary, the participation of over 30 Nyangumarta men and women can now be seen as significant to the success of the venture.

Fig 2: Elizabeth Campbell operating the Floyd camera, 8 second exposure. Photograph: Ernest Brandon-Cremer. Courtesy Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, P3549-201. Colourised image.

The confirmation of Einstein’s theory of general relativity opened up new frontiers for the understanding of our universe, creating a new stream of science called cosmology and made possible the interpretation of many recent discoveries, such as black holes.

There are five total solar eclipses which can be seen from Australia in the next 17 years. You can find out more about these and the history of total solar eclipses in Australia in the book “Eclipse Chasers”, forthcoming in early 2023, from CSIRO Publishing.

Acknowledgements:

“Expedition for the Observation of the Total Solar Eclipse of September 21, 1922, by the Members of the New South Wales Branch of the British Astronomical Association”. Introduction, Memoirs of the British Astronomical Association, 24, 83–85.

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1924MmBAA..24Q..83

Campbell WW (1923) “The Total Eclipse of the Sun”, September 21, 1922, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 35, 203, 11–44.

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1923PASP…35…11C

Campbell WW, Trumpler R (1923) “Observations on the Deflection of Light in Passing Through the Sun’s Gravitational Field, Made During the Total Solar Eclipse of September 21”, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 35, 158–16.

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1923PASP…35..158C

Chant CA (1923) “The Eclipse Camp at Wallal”, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 17, 1–9.

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1923JRASC..17….1C

Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology (Australia) (1922) The Total eclipse of the sun, 21st September, 1922, issued under the authority of the Minister of State for Home and Territories by H.A. Hunt, Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology Melbourne.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-52816234

Fascinating! Thank you for this interesting article.