On this International Women’s Day in 2022 Dr Toner Stevenson reveals what we can learn from the past when we investigate women’s, sometimes unacknowledged, contribution to Australia’s astronomical history.

The theme for International Women’s Day 2022 is gender equality today for a sustainable tomorrow #BreakTheBias. What this means for my research into women in astronomy in Australia’s past is to find the women who were active participants but not always acknowledged for their contribution to scientific research. Whilst doing this my aim is to reveal what women can learn from the past.

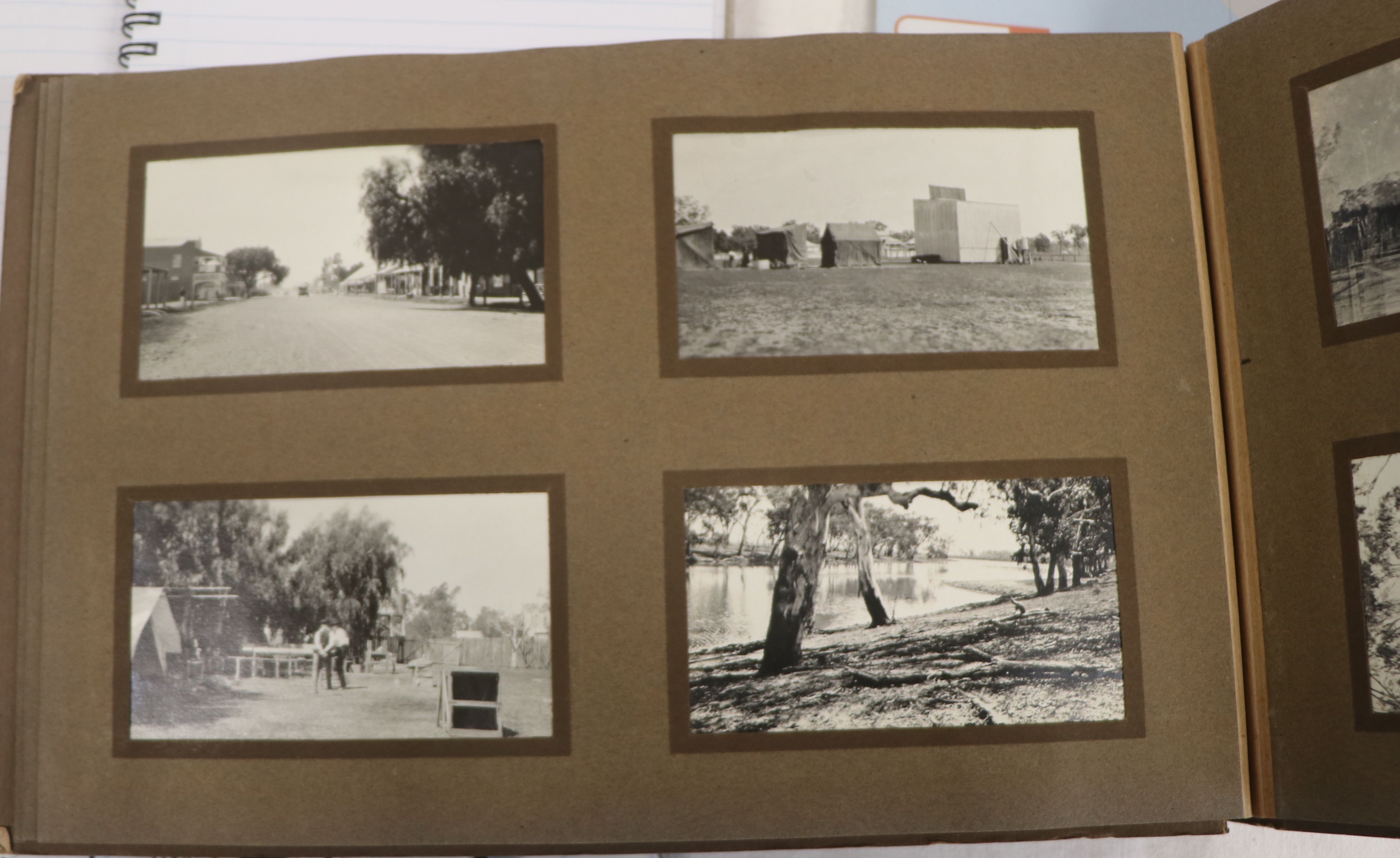

This blog post looks back a century to tell the story of an adventurous journey of 965 kilometres undertaken taken by Miriam Chisholm (1901-1979) in September 1922 to observe and document a total solar eclipse on the line of totality near Goondiwindi, southern Queensland. Miriam was a keen photographer, not a scientist, but because she was curious and a twenty-one-year-old seeking adventure with an equally curious friend, Freda Tindal, and Frank Chisholm, her father, what might have been a daunting trip became possible.

The reason we know about Miriam is that she was keen to publish her findings (1). Even though other women were involved in official eclipse expeditions, doing scientific work, Miriam, with Freda as co-author, was one of the few women to have published a comprehensive report of the 1922 eclipse alongside the observations of the mostly male members of the British Astronomical Association (NSW Branch).

Miriam and her father packed up their very modern car which had been specifically altered for the trip to enable only three passengers, and therefore more room for luggage. It had seats that could be removed to put around a collapsible table and other conveniences which Frank patented. This enabled the group to travel in comfort with a 3-inch (76mm) aperture telescope, a sturdy tripod, camera, stop watches, a thermometer and essentials such as food, water and plenty of enthusiasm. They headed off from their home in Goulburn to Glen Innes to pick up Miriam’s school friend and fellow horse enthusiast, Freda Tindal. Chisholm’s father documented the journey (2) with particular attention to the state of the roads, the condition of the country which he remarked was in drought, the waterways, cultivation, pests such as prickly pear and types of timber. They had some setbacks on the journey, one of which was when they became bogged near Styx River between Kempsey and Armidale, and they lost four days of travel time due to bad weather. All the way Miriam photographed the journey.

Lunch near Coffs Harbour, Frank and Miriam Chisholm, photographed with self-timer, M. Chisholm, 1922. Courtesy Goulburn District Historical and Genealogical Society.

On the eclipse day, Thursday 21st September 1922, they were still on the road to Goondiwindi Racecourse to join other observers. But half an hour before the eclipse was due to start, just after 3pm, they still had 22 kilometres to go. So they stopped the car and found an observing site with a clear view. The westerly wind was strong but died down as the eclipse began so the weather was perfect. Just like the official parties from the government Observatories, who were also viewing the eclipse, each member of the team had their job to do.

As the partial phases of the eclipse, when the shadow of the Moon takes a bite out of the Sun, began they had just finished setting up and as totality approached they spread out a sheet on the ground and Miriam and Freda timed the shadow bands. Freda noted the stars that were visible during totality which included the Southern Cross constellation; she noted four planets, Mercury, Venus, Saturn and Jupiter. Freda drew the Corona, which is the light around the edge of the Sun during totality, noting, “The light from the Corona did not end abruptly. It seemed to melt into the sky…the colour of the streamers was pearly white.” Freda observed the colour of the light and timed totality’s third and fourth contacts as the Moons shadow left the Sun.

Eclipse observing site, 1922. The sheet for observing the shadow bands is in the foreground and Frank Chisholm is fixing a small telescope to the car. Photo M. Chisholm. Courtesy Goulburn District Historical and Genealogical Society.

Both Miriam and Frank Chisholm viewed the event through telescopes, one of which was mounted on a tripod, the other was fixed to the windscreen of the car. They also photographed and sketched the eclipse as they observed, looking in particular for Baily’s Beads, which are visible a few seconds before totality. Miriam noted the colour of the landscape, the behaviour of animals and birds, and measured the temperature which dropped from 20℃ to 15.5℃.

According to their timing, eclipse totality was a little over 3 minutes and 15 seconds. None of Miriam or Frank’s photographs taken during the eclipse were very successful, which she noted was because there were just too many things to do in a very short time, and some decisions that did not work as well as she thought. Overall, however, the entire expedition was highly successful and their observations were comparable to those of much more experienced amateur astronomers.

A page from Miriam Chisholm’s photo album, 1922 Eclipse. Photo T. Stevenson.

Most importantly the experience was fully documented with a published paper which acknowledged herself and Freda Tindal as authors. Miriam’s photographs appeared in newspaper reports about the journey written by her father and throughout her life she documented the countryside, her family and travelled widely overseas. Like astronomers she kept meticulous records.

With thanks to the Goulburn District Historical and Genealogical Society Inc. for access to their archives and Miriam Chisholm’s photographic album from 1922. The National Library of Australia also has an archive of Miriam Chisholm’s photographs.

REFERENCES

1. Chisholm M., Tindal F., 1924, Expedition for the Observation of the Total Solar Eclipse of September 21, 1922, by the Members of the New South Wales Branch of the British Astronomical Association. Memoirs of the British Astronomical Association 24, pp. 94–100.

2. 1922 ‘By Car’, The Sydney Stock and Station Journal (NSW : 1896 – 1924), 31 October, p. 4.

If you would like to read more on women in astronomy, Toner writes:

I have found it important to understand that even if women were rarely heard because they were behind the scenes, and often physically as well as academically ‘hidden’, they had creative input, hopes and dreams. Past #IWD blog posts and videos include:

Women who supported male astronomers

Women who measured the stars and who were called ‘computers’

Women who stood up for each other against bullying in the workplace

Women who broke down education barriers

A woman who spent her life championing equality

Dr Toner Stevenson is an Honorary affiliate in the History Department, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, The University of Sydney. She is co-editor and author of a new book about Eclipses due for release in early 2023.