Guest post by Sydney Observatory Resident Catherine Sarah Young. Young uses her background in molecular biology, fine art, and interaction design to create interdisciplinary and experimental artworks on the environment. She is currently a Scientia Scholar at UNSW in Sydney undertaking a PhD in Art and Design, an Obama Foundation Leader for Asia-Pacific, and part of TeamHB6 of Homeward Bound, a leadership program for women in STEM set in Antarctica.

Entering Sydney’s lockdown of 2021, this time because of the Delta variant of the coronavirus, meant exiting the Sydney Observatory residency for me in the physical sense. I sadly bid farewell to my room in the Observatory, barely used and whose sticky locks I had just gotten used to. I, like many of us, had been accustomed to the changing situation presented by the COVID-19 era. The residency system as well has been transformed and I had to be mostly confined to my flat in Paddington and its five-kilometre radius.

For my residency, I had been interested in doing research on Mars. As an artist who works on environmental issues such as climate change, the human ambition to investigate and to voyage to the Red Planet become increasingly important. Do we see Mars as Planet B, as we are currently destroying our Planet A? What might we learn from a planet that so many governments and billionaires want to set foot on? What does it mean for us to seek to be a multi-planet species? And how can we ensure that we remember our human and Earthbound origins as we do so?

Like an astronaut preparing for confinement, I had taken photos of every single object in the Observatory before pursuing my research virtually, as though I had wanted to create a personal archive in my pocket before the gates of the Observatory were closed to me for the time being. In many ways, confined to our homes and besieged with the seemingly perpetual anxieties of contagion, conflict, and catastrophe, we are astronauts on planet Earth, wondering where to land and when we can leave the spacecraft that our homes have become. We are in many ways at war with ourselves, and thus it may seem a bit poetic that the Red Planet we want to go to is named after the god of war in Roman mythology. In the years to come, the tension between our species as Earthbound creatures and our species as interstellar voyagers will become more apparent.

Figure 1. ‘Mars’ porcelain figure made by William Duesbury & Co. c1760. MAAS Collection.

From Sydney to Mars

More than a century ago, a fellow Paddington resident Walter Frederick Gale (1865-1945) had also been interested in Mars. Gale was a banker and astronomer, educated at Paddington House School and had a lifelong interest in astronomy because of his father’s encouragement and the appearance of the Great Comet in 1882.1 At seventeen years old, witnessing this powerful force in the sky created a lasting impression, and he discovered several comets in his lifetime.2 A member of the British Astronomical Association (BAA) (now known as the Sydney City Skywatchers), Gale led an expedition to Queensland to see the total solar eclipse of 1922.3

Figure 2. Photograph of Walter Frederick Gale and the eclipse expedition of the British Astronomical Association in Queensland, 1922. Gale is third from the left. MAAS Collection.

Ten years later, Mars was exceptionally close to the Earth, making it an excellent opportunity for it to be viewed through telescopes. The BAA in London reviewed the various drawings submitted to them by space enthusiasts, and Walter Maunder, Director of the Mars section, remarked on the superior quality of Gale’s submission.4 Gale further created glass slides of Mars and other astronomical observations, which are in the Observatory collection. The desire to discover and to record the distant planets and other celestial bodies persists in human history, and the Observatory hosts not just archives of the past, but also current images of space taken by professional and amateur astrophotographers.

Figure 3. Drawings of Mars by Walter Gale on 6 August 1892 at 12:30 am Sydney Mean Time (SMT) and 7 August at 11:15 pm EST. Image from the Illustrated Sydney News of 18 February 1893 p18.

Despite being confined to both Earth and our homes, places like Sydney Observatory create space for us, who, like Gale, direct our curiosity to the skies. In the beginning of the year before the lockdown, we, the residents, had the cool opportunity to tour the Observatory with curator and astronomer Dr. Andrew Jacob. The highlight of this was looking into the Schröder refracting telescope, which is the oldest working telescope in Australia. It was first installed in the South Dome in 1874 to observe the transit of the planet Venus as it crossed the face of the Sun.5 Opening the dome was a special experience for me as a resident, as I had visited the Observatory several times before but never had access to this part until then.

Figure 4. Opening up the South Dome—a residency highlight! Photo by Kate Rees.

Escaping to another planet may be the dream of many an intrepid explorer but I like to think of Mars missions in relation to improving our Earth mission in parallel. We may not get it exactly right the first time, but eventually we get there, such as in the case of Mars-3, the first spacecraft to make a successful landing on the Martian surface. Hopefully, we get it right here on Earth, too.

Figure 5. A 1:2 scale model of the USSR spacecraft Mars-3. Pre-1985. MAAS Collection.

Water and planets

The spirit of exuberant curiosity of Walter Frederick Gale exists in us, which may even emerge through the constraints imposed by lockdown. For many of us in confinement, there is an impulse to record the minutiae of our lives—the daily walks, the food made and ordered online, the workouts, the Zoom calls with loved ones we cannot see in person. Like astronauts, albeit of the accidental kind, we track various activities, once so mundane in the Beforetime when masks were not mandatory and human contact was something we took for granted. These activities are transformed into special moments, proof that the day even happened at all. We pass the time like astronauts on the way to Mars, recording plant growth, calories burned, and remaining supplies, with the goal of reaching the other side though unknowing when this will be at all. And these activities are for us who are fortunate enough to still have our basic needs met while our social systems are tested in these pandemic times.

In researching Mars in relation to life on Earth, one of the first things we think about is water. In the American science fiction drama Away that streamed on Netflix last year, there is a scene where Commander Emma Green, played by Hilary Swank, is in conversation with her Earthbound husband, who holds his phone outside his car so that she could hear the sound of rain. The scene cuts to Green imagining a rain shower in the spaceship. Few things are as Earthly as the sight of rain clouds, and this photograph in the late 19th century by Observatory photographer James Short is a rare surviving example of early meteorological photography.

Figure 6. Rain clouds by Observatory photographer James Short 1891-1900. MAAS Collection.

Figuring out rain on Earth helps us understand the gravity of the water situation on the dry Red Planet. I was fascinated by the collection of rain gauges of the Observatory which illustrate similarities and differences of rain measurement. Quantifying rain persists in civilisations throughout history as this helps plan for agriculture, from beautifully crafted ones like the Korean rain gauge from 1442, to various metal gauges in later centuries, to two measuring cylinders from the 19th century, to the delightfully named pluviograph.

Figure 7. Replica Korean rain gauges. The originals were designed in 1442 by Jang Yeong-sil whose patron was King Sejong, ruler of the Choson Dynasty. MAAS Collection.

Figure 8. Metal rain gauge. Date unknown. MAAS Collection.

Figure 9. Two rain gauge measuring cylinders. These were designed by Angelo Tornaghi for Sydney Observatory. He was born in Milan and arrived in Sydney in 1858 to supervise the adjustments of the Observatory’s Negretti & Zambra instruments. MAAS Collection.

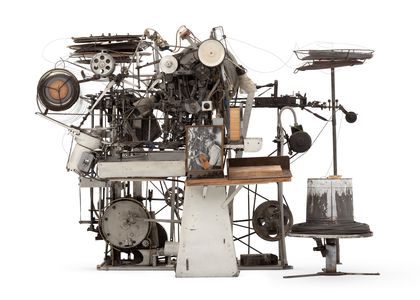

Figure 10. A rain gauge or pluviograph made by either Angelo Tornaghi or one of the Observatory staff and was used in the Observatory before 1900. By 1860, rainfall and other weather observations were collected every month from around New South Wales and sent to the Observatory. This pluviograph is especially significant because of its pioneering role in Australian science that connected astronomy, meteorology, and technology. MAAS Collection.

The permanence of temporary phenomena

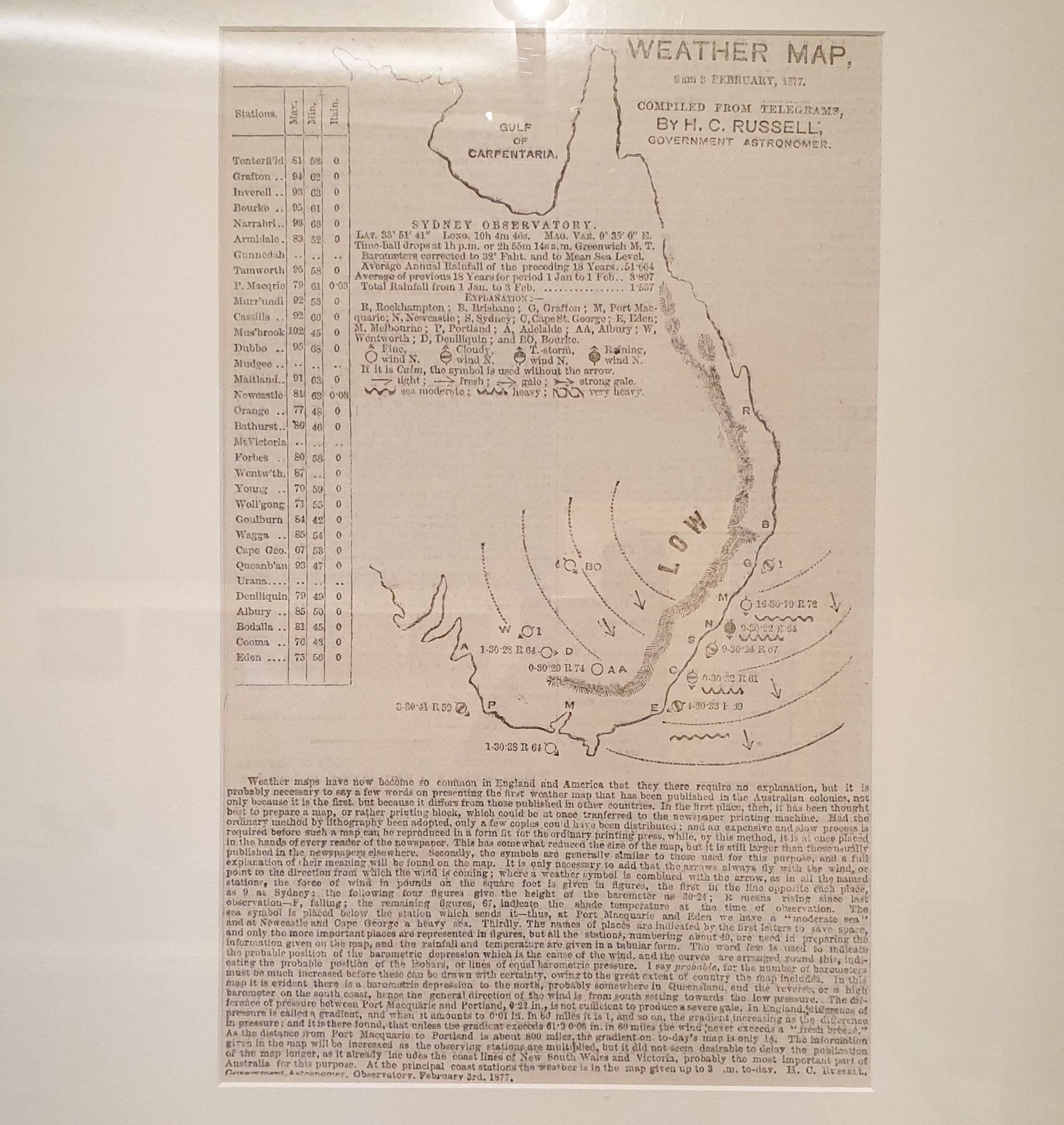

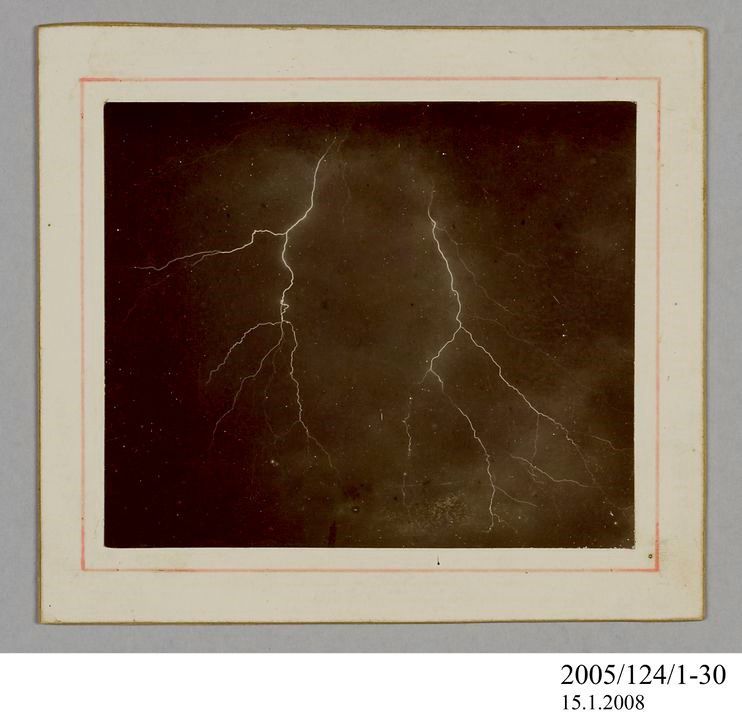

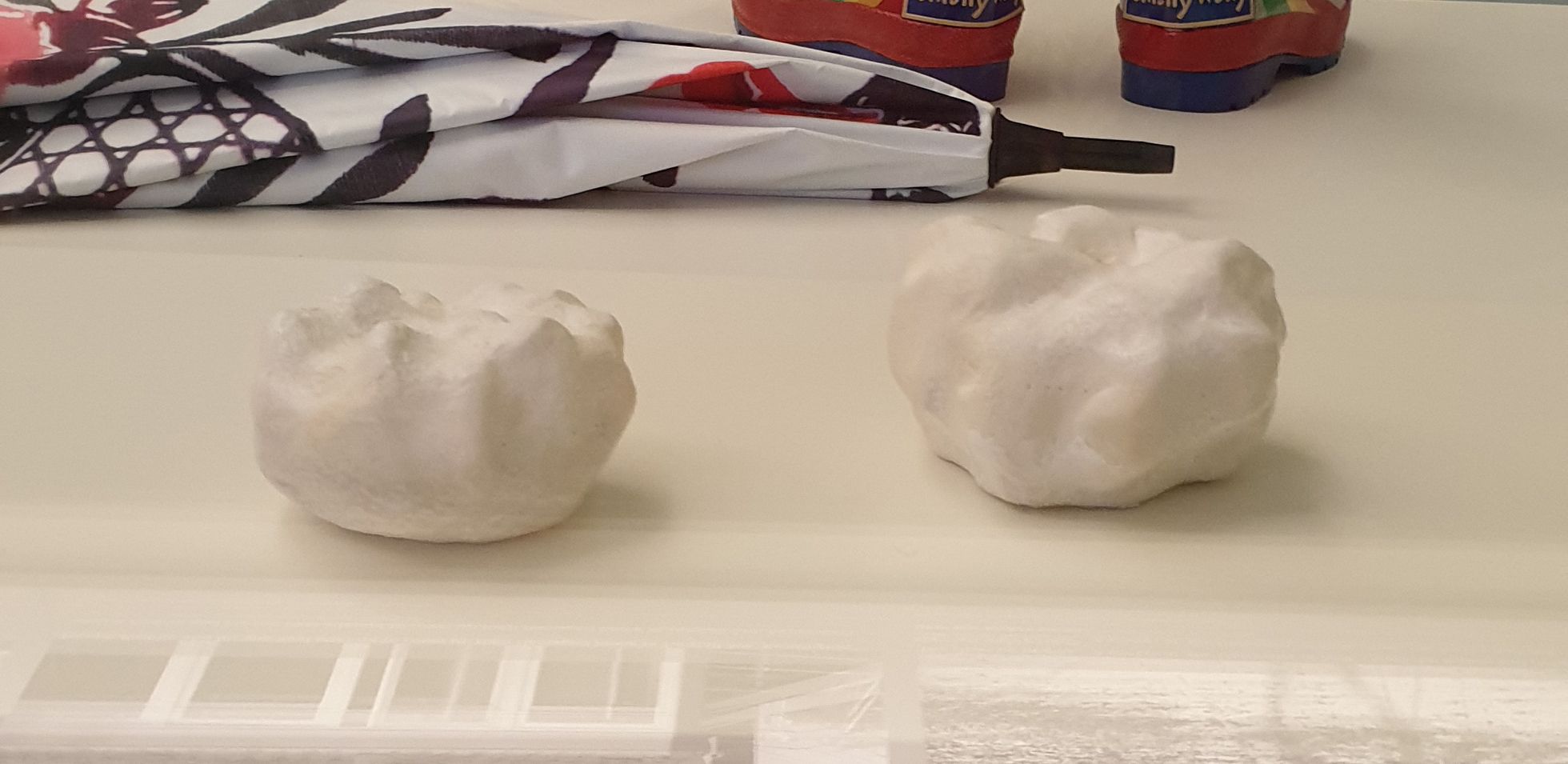

Creating permanent archives of temporary phenomena helps us understand the systems that govern the workings of the Earth. My favourite exhibition room in the Observatory contains some of these rain gauges as well as various artifacts from different times in the history of Sydney that focus on weather. Here you can find the first weather map of Australia made by Henry Chamberlain Russell made 1877. To compile the map, Russell referenced weather information telegraphed to the Observatory from 40 meteorological stations across New South Wales. There are also photographic records of clouds and lightning, as well as models of hailstones that fell in the storm of April 1999, with the largest one being 8.5 cm in diameter. This makes me wonder about the future maps and instruments we may use someday in Mars, and what adaptations we will eventually have.

Figure 11. The first weather map of Australia made by Henry Chamberlain Russell, the third New South Wales Government Astronomer and the first Australian-born one.

Figure 12. Photograph of lightning used by James Short, 1908. MAAS Collection.

Figure 13. Model of hailstones that fell in 1999. Original casts made by Mike de Salis, Bureau of Meteorology, NSW Office. Display Models by Iain Scott-Stevenson.

Our search for water continues in Mars and also links with Walter Frederick Gale, as a crater on the Red Planet is named after him. NASA chose the Mars rover Curiosity to land on Gale Crater because of signs that it may have contained water in its history.6 The Gale Crater is estimated to be about 3.5-3.8 billion years old which may be a dry lake. In the centre of the crater rises the mountain Aeolis Mons, and in between this mountain and the crater’s northern perimeter is the plain Aeolis Palus. NASA’s Curiosity Rover landed in Aeolis Palus on August 6, 2012. This spot has since been named Bradbury Landing, named after author Ray Bradbury.7

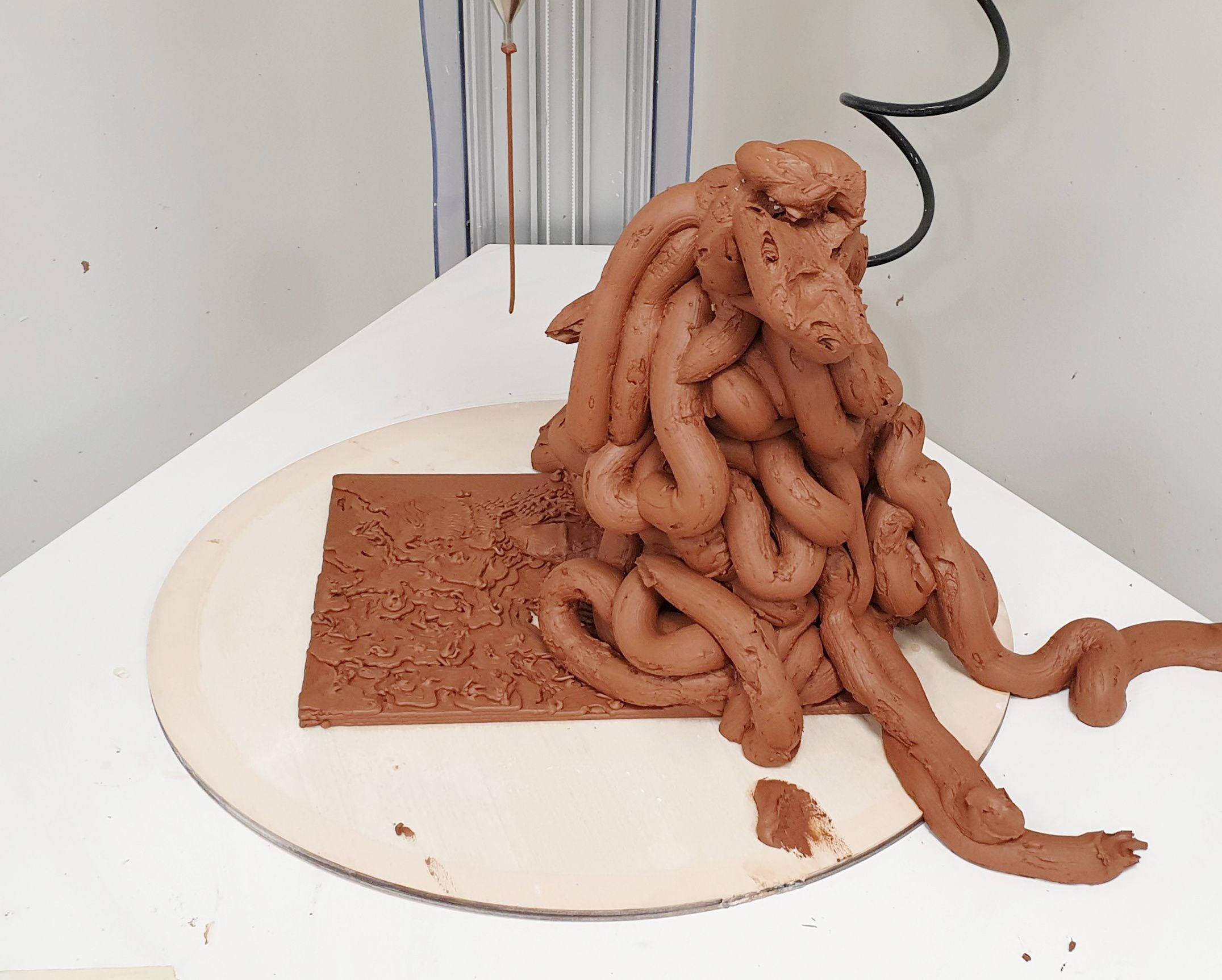

I realised while discussing my project with the Sydney Observatory staff that I had actually 3D printed the Gale Crater several weeks ago. In the UNSW Design Futures Lab where I conduct some of my research, I had been experimenting with 3D printing Martian landing sites. NASA has an open-source website that contains various 3D models. Printing Martian landscapes using clay from planet Earth felt like connecting the two celestial bodies together. Like Martian landings, we cannot get it right the first time, as you can see in this incident where the printer, as unpredictable as our current times, regurgitated the clay onto my board.

Figure 14. A 3D printing accident. Photo by Catherine Sarah Young

But eventually, we get it right!

Figure 15. 3D printed and fired Gale crater. Photo by Catherine Sarah Young

I have a one last thought on water and planets (and also billionaires and pandemics). There is a quote that is going around which says, “We are in the same storm, but not in the same boat.” Similarly, we are in the same space but not the same spacecraft. Confinement to our homes in a pandemic reveals the various ways in which we need to make life more equitable for all of us to be ok while we continue with our interstellar ambitions. In the time of Walter Frederick Gale, Mars was alien territory. Now, it is slowly but surely within our reach. We know where we want to land in both Earth and Mars, but the question is: how?

References

1 Harley Wood, ‘Gale, Walter Frederick (1865-1945)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1981. Accessed online 24 18 August 2021: https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/gale-walter-frederick-6269

2 Obituary, Walter Frederick Gale, British Astronomical Association, 1 June 1945. Accessed 18 August 2021,

http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1945JBAA…56…18

3 Geoff Barker, ‘Photograph of Walter Gale and the British Astronomical Association eclipse expedition,’ October 2008, accessed 18 August 2021: https://collection.maas.museum/object/382076

4 Nick Lomb, ‘Walter Gale and the Landing of Curiosity’, 7 August 2012, Accessed 18 August 2021: https://www.maas.museum/observations/2012/08/07/walter-gale-and-the-landing-of-curiosity/

5 Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. The Story of Sydney Observatory. Sydney: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, 2018.

6 W. E. Dietrich , M. C. Palucis , T. Parker , D. Rubin , K. Lewis , D. Sumner , and R.M.E Williams. 2014. “Clues to the relative timing of lakes in Gale Crater.” (Report). The Eighth International Conference on Mars, Pasadena. https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/8thmars2014/pdf/1178.pdf

7 Dwayne Brown, Steve Cole, Guy Webster, D.C. Agle, “NASA Mars Rover Begins Driving at Bradbury Landing, NASA, 22 August 2012. Accessed online 18 August 2021: https://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2012/aug/HQ_12-292_Mars_Bradbury_Landing.html

Thank you for that interesting and thought-provoking post Sarah.