Guest post by Artist in Residence, Lily Hibberd

Lily Hibberd is an interdisciplinary artist and writer working with frontiers of time and memory. Her projects are developed in long term place and community-based collaboration, and research with local artists, scientists and historians through combinations of performance, writing, painting, photography, sound, moving image and installation art.

This blog has been created for ‘Boundless – out of time’, Lily’s month-long artist and research residency at Sydney Observatory. View all of Lily’s posts here and read the introduction to Boundless Remapping Sydney Meridian. Presented by Powerhouse Museum as part of NIRIN, the 22nd Biennale of Sydney 2020.

At Erskine St. head for the Wynyard pub … no, it’s not beer o’clock just yet! Cross over to the Officeworks store, behind the 4th pillar, just before the laneway is Station 11 – a little detour from the meridian – a triangulation to be precise.

My fascination with the meridian was only deepened by meeting Astronomer Suzanne Débarbat in 2012, which later developed into a close collaboration for an exhibition at the Musée des arts et métiers in Paris in 2015. A year prior to my first visit to Paris Observatory, I had already attempted to walk the line through the city of Paris – on a hot late summer’s day in September 2011. This effort, I’m sure you will pick up, is one of the inspirations for this present day reconstruction of Sydney Meridian through an idiosyncratic mapping exercise.

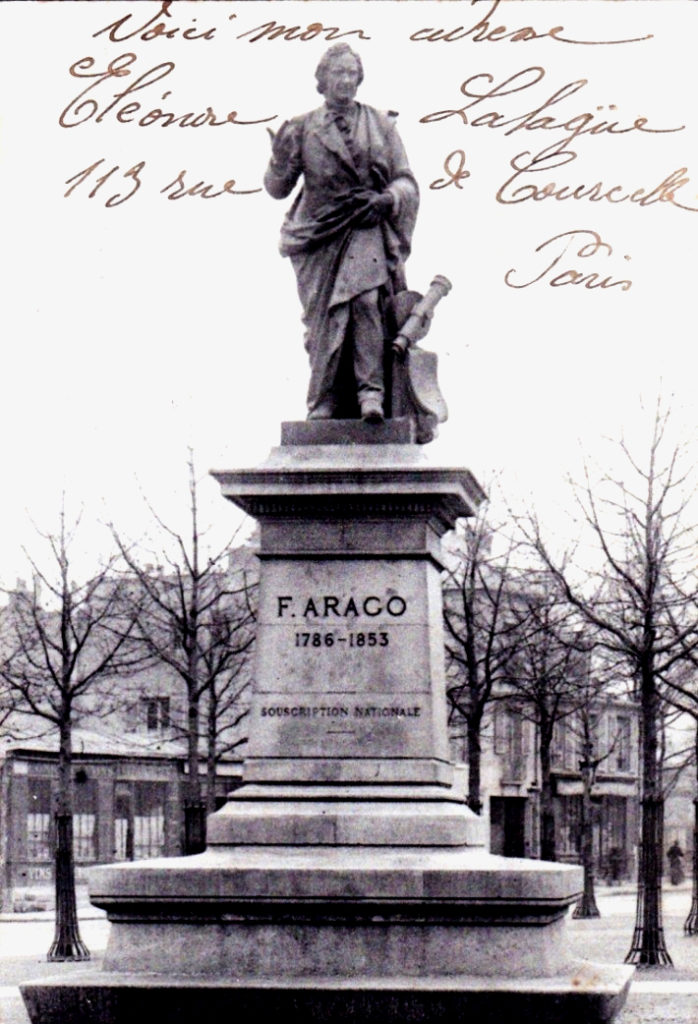

Today, the Meridian of Paris is a better known secret, but there was much less information online when I first went looking for details – most of which confused it with Dan Brown’s fictitious ‘Rose Line’ (though both pass by the Pyramid of the Louvre Museum, there is no other connection). I found out instead that the Paris Meridian had been transformed into an amazing work, ‘Homage to Arago’. In 1994, Netherlands artist Jan Dibbets had been commissioned by the city of Paris to create a memorial to François Arago – whose original bronze statue was melted down in 1942 by the Vichy Régime who had been given an order to reprise this metal for arms during the World War II German occupation of France.

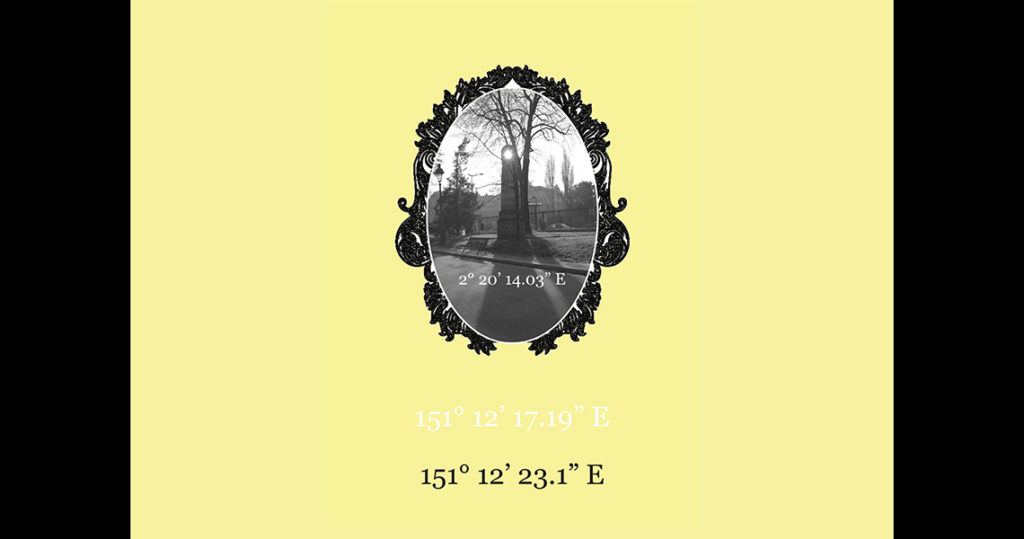

Dibbets created a work in keeping with this annihilation, for which he fixed on the perfect form in the embodiment of the imaginary meridian line. Making a kind of anti-memorial, he laid 136 bronze medallions along the nine kilometre section between the two peripheries of the centre of Paris. In 2011, I only had a printout of a guide made by a couple of Netherlands fans who had attempted to geolocate all 136, with some rather allusive instructions in Dutch.

A large number of medallions were missing – stolen, lost, or unintentionally removed during roadworks – and it was additionally impossible to walk a straight path because the imaginary line intersected city buildings and major institutions, like the Musée du Louvre, making the walk a circuitous venture. At least each medallion had been furnished with a north-south direction, the N and the S seen here, helpful for aligning yourself with the next medallion.

While this is a fascinating re-enactment exercise that also sublimates the body in line with the metric system, the questions of the contradictions and the imperial intent the system to discipline both time and human life remain unanswered in any of this work so far.

Seven years later, Australian artist Sara Morowetz undertook a performance walk of the entire French meridian, as part of her project Étalon, for which she remeasured the meridian using GPS, sending field report postcards to the director of the Musée des arts et métiers all along the long march, over four months in 2018. Meanwhile, yet another homage to Arago was commissioned in 2016, with a statue by Belgian artist Wim Delvoye. The City of Paris however maintained that this object had to be placed elsewhere, so that the base might remain empty in memory of the missing bronze.

Way back at Station 2, the debate about the Sydney Observatory markers revealed how easily significant objects can vanish both materially and from public memory. Like most other meridians determined from the fixed point of an observatory, Paris Meridian has a number of trigonometric markers that are still standing. Known in French as a ‘mire’, two still stand on the Paris meridian line, one each for the northern and southern orientation. Today, they are obscure objects in the landscape and probably only noticeable to those chasing the meridian line.

The same as Arago’s tower, the premise of these markers was to realign the meridian telescope from a longer distance. Over time, more elaborate ornamentation was contrived to enhance visibility, such as shiny metallic discs. In the case of the southern mire in Parc Montsouris, a circular aperture was formed out of stone, through which the sun would shine. But this only occurred at the right time, producing a supernatural effect, which I waited for one morning, as you see here in the poster for Station 11. Maybe the people of Formentera were right to fear the masonic arts that Arago brought to the hill of La Mola!