The Powerhouse Museum collection contains material relating to architecture and the built environment, of local, national and international significance. The collection includes scale models, design archives, plans, drawings, photography and interior fittings, with projects ranging from iconic buildings by award winning, internationally recognised Australian architects Glenn Murcutt, Harry Seidler and John Andrews, to social housing and civic projects of public interest. Architectural models form an important part of the architecture and built environment collection, and the Museum has many fine examples of conceptual, working, and large-scale presentation models that illustrate this craft.

A central part of professional architectural practice, model-making is used to prototype, develop and refine architectural designs at a small scale. At the preliminary design and development stages, models allow architects to conceptualise and problem-solve in three dimensions. They can also be used to investigate structural and technical problems and explore interior and spatial issues. Architectural models can also support the development of highly complex sculptural forms, unable to be resolved by drawings alone.

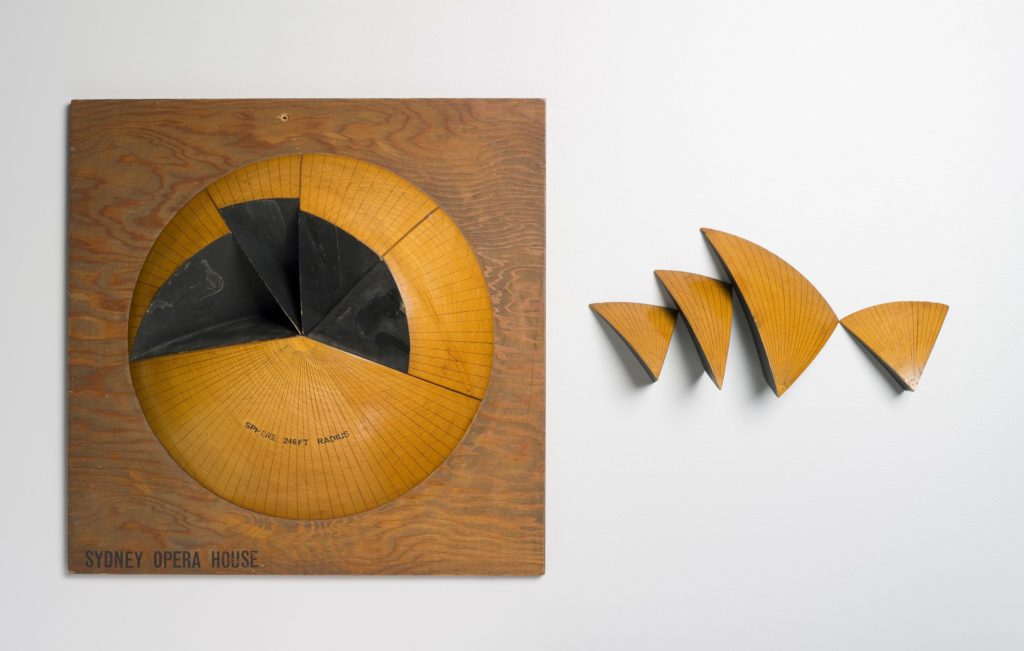

This process is demonstrated by the Sydney Opera House model held by the Powerhouse Museum. The handcrafted wooden display model designed by Danish architect Jørn Utzon was used to illustrate the Sydney Opera House sail design to Dutch engineer Ove Arup in the 1960s (below). In his essay on the roof geometry model of the Sydney Opera House, curator Matthew Connell describes how the ‘model demonstrates, with remarkable efficiency and clarity, the final geometric solution for the shape of the Opera House and how the protracted problem of the construction of the ribs required to support the great shells is resolved.’

In recent years the use of computer aided design (CAD) software for drafting and 3D-modelling in architectural practice has changed the way many models are made, with the introduction of CNC milling machines and laser cutters. At the same time, CAD and computer modelling has ensured that the design of buildings have become more ambitious, with sophisticated parametric and algorithmically generated structures gracing our skylines impossible to imagine only a decade ago.

Even with the availability of advanced computer modelling, many contemporary architects continue to make rudimentary physical models to explore complex ideas, for instance OMA’s Casa da Música concert hall in Portugal designed in the late 1990’s – the adoption of the geometric polystyrene foam model echoes that of the wooden opera house model constructed 40 years previous. Although scale models produced by hand are declining in favour of digitally fabricated models, 2D computer modelling has not yet successfully replaced the physical model.

The Musuem’s collection holds models of urban design and planning, including large-scale housing projects such as the Kooralbyn Hillside Housing development site model by Harry Seidler and Associates (above), which illustrates the distribution and arrangement of Seidler’s buildings within the surrounding urban landscape. Also, an extensive design archive of 1960s and 1970s project home builders Pettit & Sevitt, which contains interior and exterior architectural photography by celebrated Australian photographer Max Dupain.

The collection also includes an example of Australian prefabricated housing design from the 1950s – a model of the display home St Ives by George Hudson which was used to display exterior paint colour schemes. Looking back at these historical models provides insight into building and construction techniques of the time, as well as the domestic lives of Australian people.

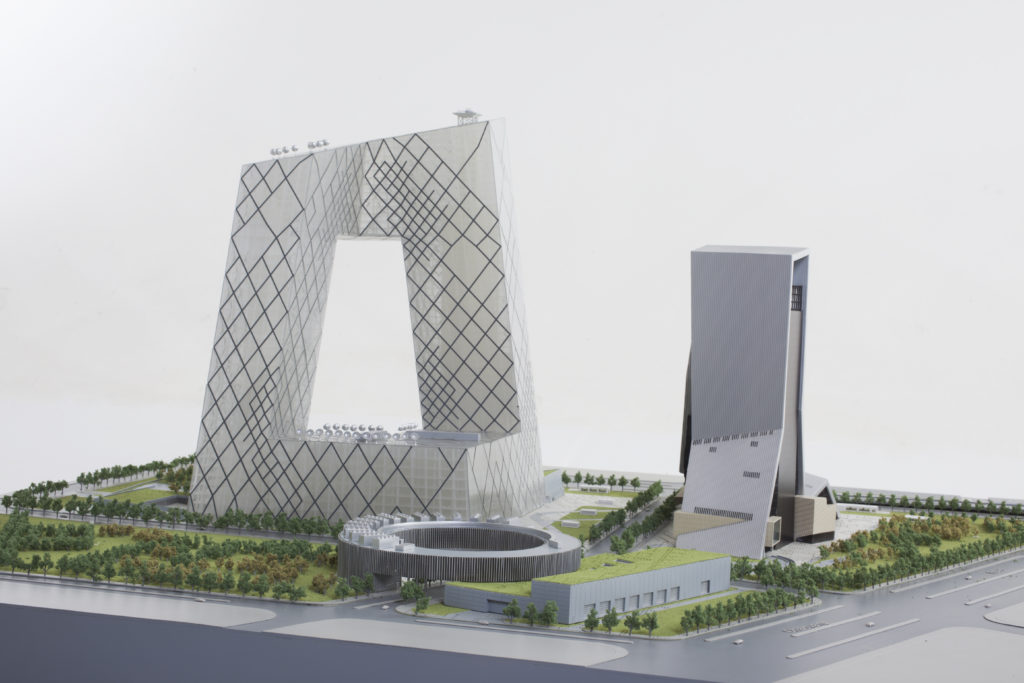

The collection also extends to the Asia-Pacific, reflecting cultural perspectives from our regional neighbours, including OMA’s China Central TV Headquarters (below), the internationally significant model of Yomeimon Gate at Toshogu Shrine Nikko, the Beijing National Aquatics Centre and a 6cm high scale model of a traditional Japanese house collected by geologist and priest Julian Tenison-Woods in 1886.

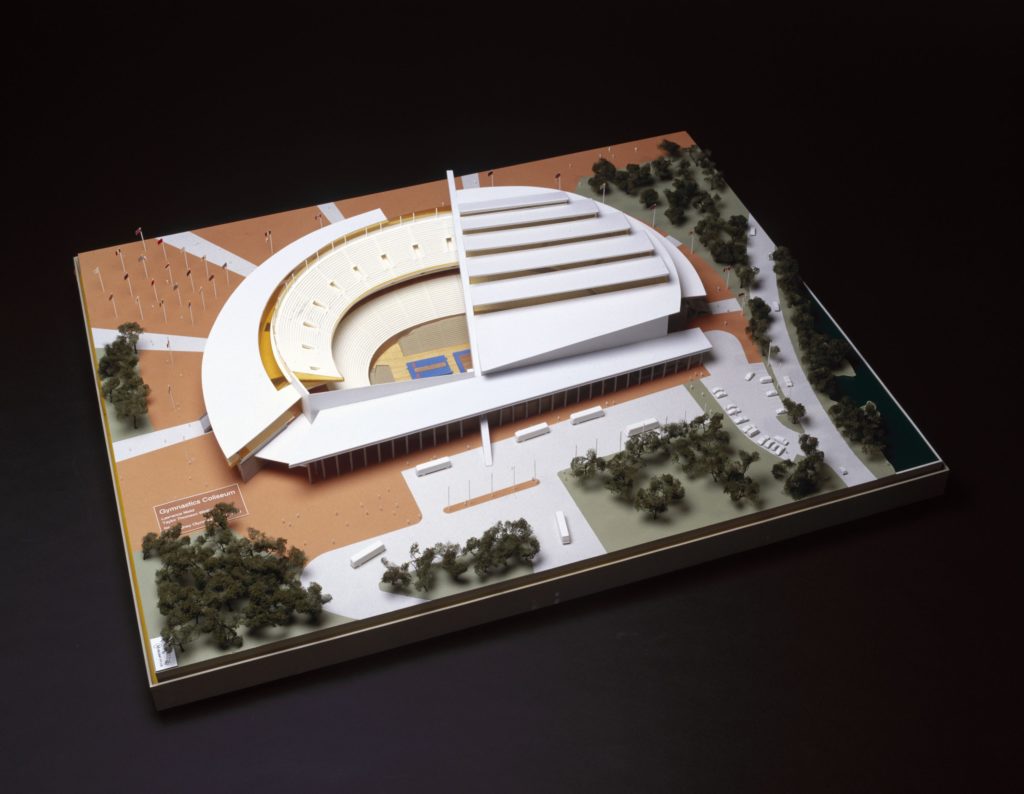

Architectural models have many uses outside design and development, they are used for presentation, marketing and documentation, and as part of competition entries, such as the models created for the Sydney Olympics 2000 Bid. In his memoir of the Olympic bid, Rod McGeoch emphasised the importance of the models to the campaign, commenting that ‘the bid office contained superb models of the venues…these models gave the big picture in a way no amount of mapping, photography or computer modelling could rival.’

The Museum also collects reproductions of buildings, bridges and urban developments that have been made for display and educational purposes. Scale models can be an effective method to communicate architectural projects in an exhibition context, and can provide insight into professional practice, serving as an excellent educational resource for emerging architects and students.

Models can also test ideas for otherwise unrealised or unbuilt architectural projects, such as 2 Bond Street by Australian architect John Andrews (below) and LAVA’s Re-Skin of UTS’ brutalist tower, which won a prize for speculative design at the 2010 World Urban Forum in Rio.

Additional information on the MAAS collection of architectural models can be found here.

Written by Keinton Butler, Senior Curator

August 2019

Resources

Roof geometry model of the Sydney Opera House, Icons, Matthew Connell, 2018. https://maas.museum/magazine/2018/10/roof-geometry-model-of-the-sydney-opera-house/

Model, site, Sydney Olympic Park, for the Sydney Olympics 2000 Bid Ltd, Sydney, 1992. Charles Pickett. https://collection.maas.museum/object/155320