The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences has just opened a display with striking objects, photographs and archival material from its extensive decorative art and design collections, to celebrate the centenary of the Bauhaus, the most influential 20th century school of design. In this post, we’ve selected a few highlights.

The Staatliches Bauhaus was founded by German architect and designer Walter Gropius in 1919 in the town of Weimar, Germany. Although it was closed in 1933 amidst the political turmoil of the Nazi-era, it fundamentally redefined the role of design in society, introducing interdisciplinary design concepts and teaching. Central to the school’s philosophy was the unity of art, craft and architecture, and the designer’s role as an agent for change.

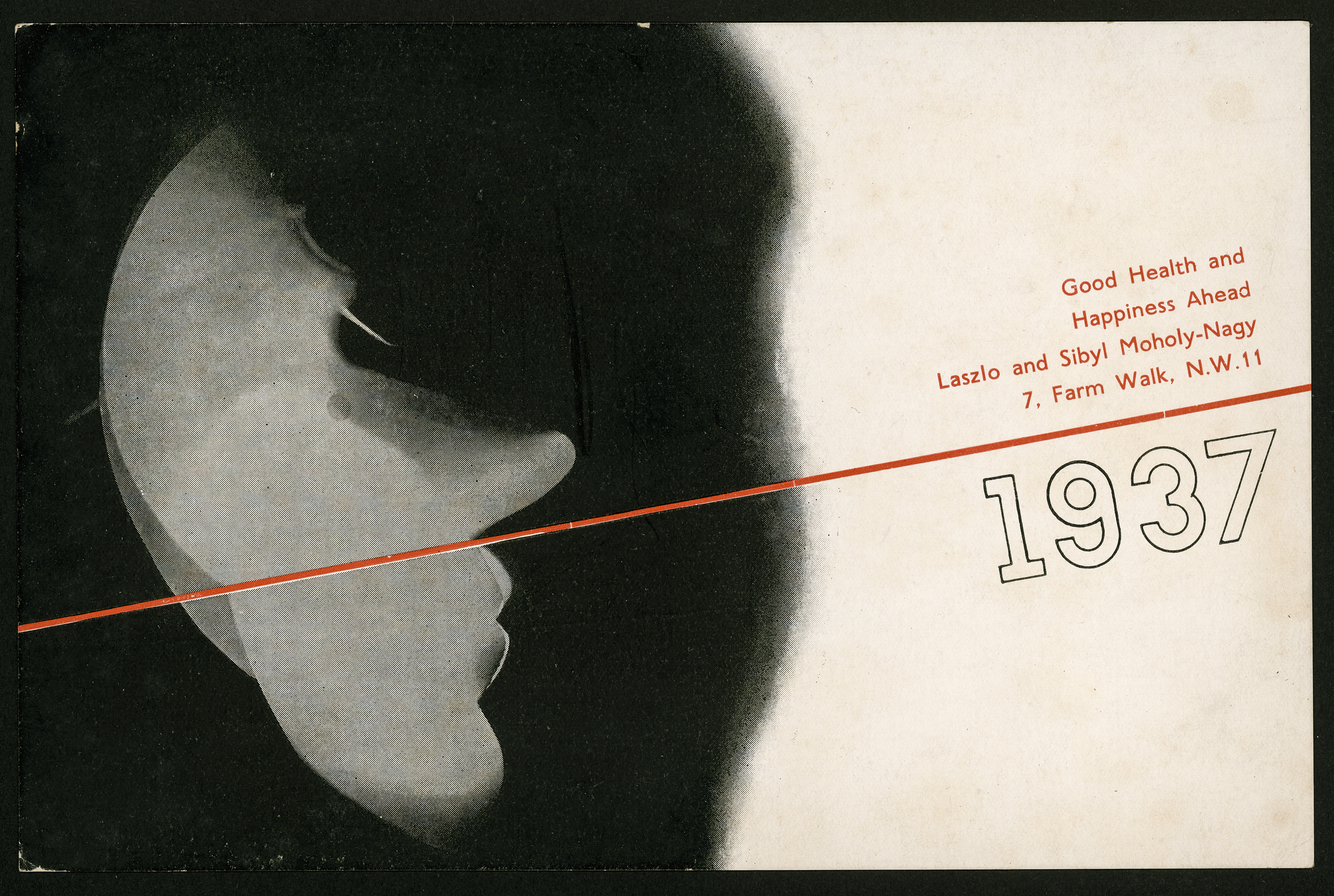

The progressive ideas at the Bauhaus owed much to avant-garde artists who came from across Europe, drawn to the Bauhaus and the exciting possibilities it offered for creating radically new forms of art and design that they hoped would inspire a better world. The cover of the Wendingen magazine and the ceramic plate illustrated below, were designed by Russian Constructivist artist Lazar Markovich El Lissitzky, who was also the Russian cultural ambassador to Weimar Germany. They illustrate his revolutionary approach to non-objective art represented through Prouns, or spatial constructions of geometric shapes and lines. El Lissitzky’s art and ideas around the transformation of all art forms for a modern society paralleled and influenced artistic experimentations of the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy who advocated for the unity of art and technology. Through the teachings of Moholy-Nagy, who joined the Bauhaus in 1923, El Lissitzky exercised a radical influence at the school.

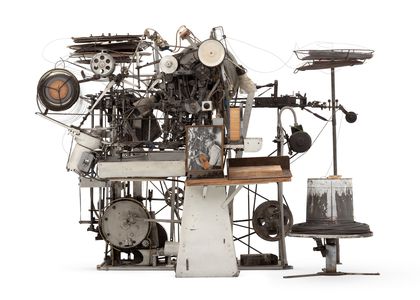

Moholy-Nagy changed the Bauhaus’ direction from an emotional apprehension of forms and colours, to a focus on rationalised and functional forms for mechanised production. His impact on students in the metalwork workshop, where Marianne Brandt studied and worked, was particularly profound. Some of the most talented students at the Bauhaus were women, and in 1928 Brandt became head of the workshop, taking over from Moholy-Nagy when he left the school to establish his own studio in Berlin.

Brandt designed this desk set soon after she left the Bauhaus at the end of 1929, when she was asked to modernise various household articles – from ashtrays to inkwells and napkin holders – for Ruppelwerk, a large metalware manufacturer in Gotha, Thuringia. Machine-cut from steel sheeting and finished in a range of bold colours, Brandt’s affordable designs proved to be highly marketable. Today, surviving objects from these modernist lines can be found in museums and private collections as examples of the application of Bauhaus ideals to industrial production.

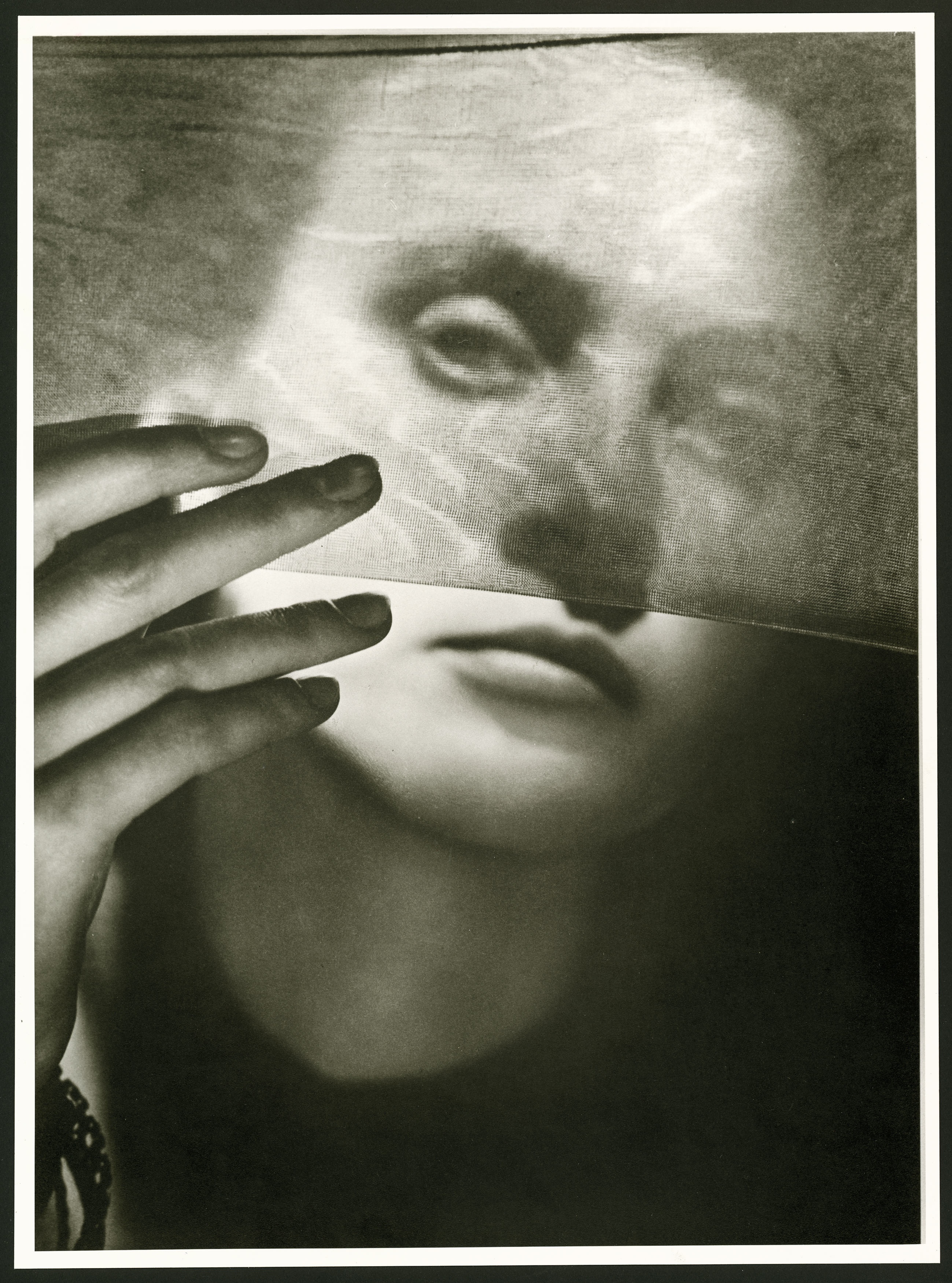

Working across disciplines, Moholy-Nagy was also instrumental in creating a new photographic style. He exploited the possibilities of the camera to break away from ‘the painterly trend’. His ideas spread to other schools where former Bauhaus instructors taught, such as the Contempora Lehrateliers für neue Werkkunst (Contemporary School for Modern Applied Arts) in Berlin, where students explored unconventional angles and extreme close-ups to allow familiar objects and architecture to be seen in new ways. Wolfgang Sievers, one of Australia’s most acclaimed post-war architectural and industrial photographers, studied and taught photography at Contempora from 1935 to 1938. Just before he escaped Nazi Germany to migrate to Melbourne via London, Sievers worked on commercial advertisements for Elbo Stockings. His photographs with their unusual details, soft shadows and sharp lines exemplify the legacy of the Bauhaus’ streamlined and modernist view of the world.

100 Years of the Bauhaus is on display until 30 June 2020 on Level 2 of the Powerhouse Museum, outside the theatrette.

Written by Eva Czernis-Ryl, Curator

July 2019