Last month the Museum opened a new exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon Landing. As the curator, I’ve spent the past 12-18 months developing this exhibition, which explores the events of 1969, and celebrates what is possibly the greatest scientific achievement of all time. It’s difficult to convey how much I’ve enjoyed curating this exhibition, and in this post I hope to give some insight into the objects on display in each section of the exhibition, and why I chose them.

Space Race

The exhibition begins with the Space Race, which erupted between the United States and the Soviet Union following the end of World War II, and follows the developments in space technology from the first spaceflights through to the Apollo program. What still amazes me is just how rapid these developments were – from the launch of Sputnik-1, the first artificial satellite, by the Soviet Union in 1957, to the first human spaceflight in 1961, and ultimately landing man on the Moon in 1969.

On display is a full-size replica of the Friendship 7 spacecraft, in which John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth. In our replica, the crew hatch has been replaced with a window, and we’ve created a viewing platform so that visitors can see inside the spacecraft to where the solo astronaut would have sat – on their back, with their knees tucked up to their chest, surrounded by an array of control panels. I can only imagine what how terrifying it must have been for the first astronauts, being launched into space in this tiny spacecraft, atop what was essentially a modified missile.

A meal package from the later two-person Gemini program – containing a very unappetising-looking cheese sandwich, salmon salad and pea soup – gives some insight into just how much was unknown in these early days of space travel. NASA was initially unsure whether humans would even be able to swallow and digest food in zero gravity, but by Gemini had developed full meal packages that could be easily consumed in zero gravity and provided the astronauts with all the nutrition they required for up to two weeks in space.

The Eagle has Landed

Alongside the rocketry technology is the computing technology that made the Apollo 11 mission possible. While the rockets are impressive for their size and power, the computing technology is astonishing for how primitive it was. The code that took Apollo to the Moon amounted to just 2MB and ran on a computer with only 2K of memory. By comparison, today’s computers typically have at least 8-16 GB of memory (thousands of times more than the Apollo Guidance Computer), and a single app update on your smartphone could easily exceed 100 MB. As someone who wasn’t alive at the time, I find it incredible what was achieved with such limited technology.

In a part of history that is so male dominated, the mathematics and computing the underpinned the mission also provide the opportunity to celebrate the many women who worked behind the scenes. This includes Margaret Hamilton, who led the software engineering team that wrote the Apollo code, along with Katherine Johnson and the teams of African-American women who did the mathematics to calculate launch and landing trajectories, spacecraft rendezvous and more. While their contributions were often not recognised at the time, without these women, the mission could not have succeeded.

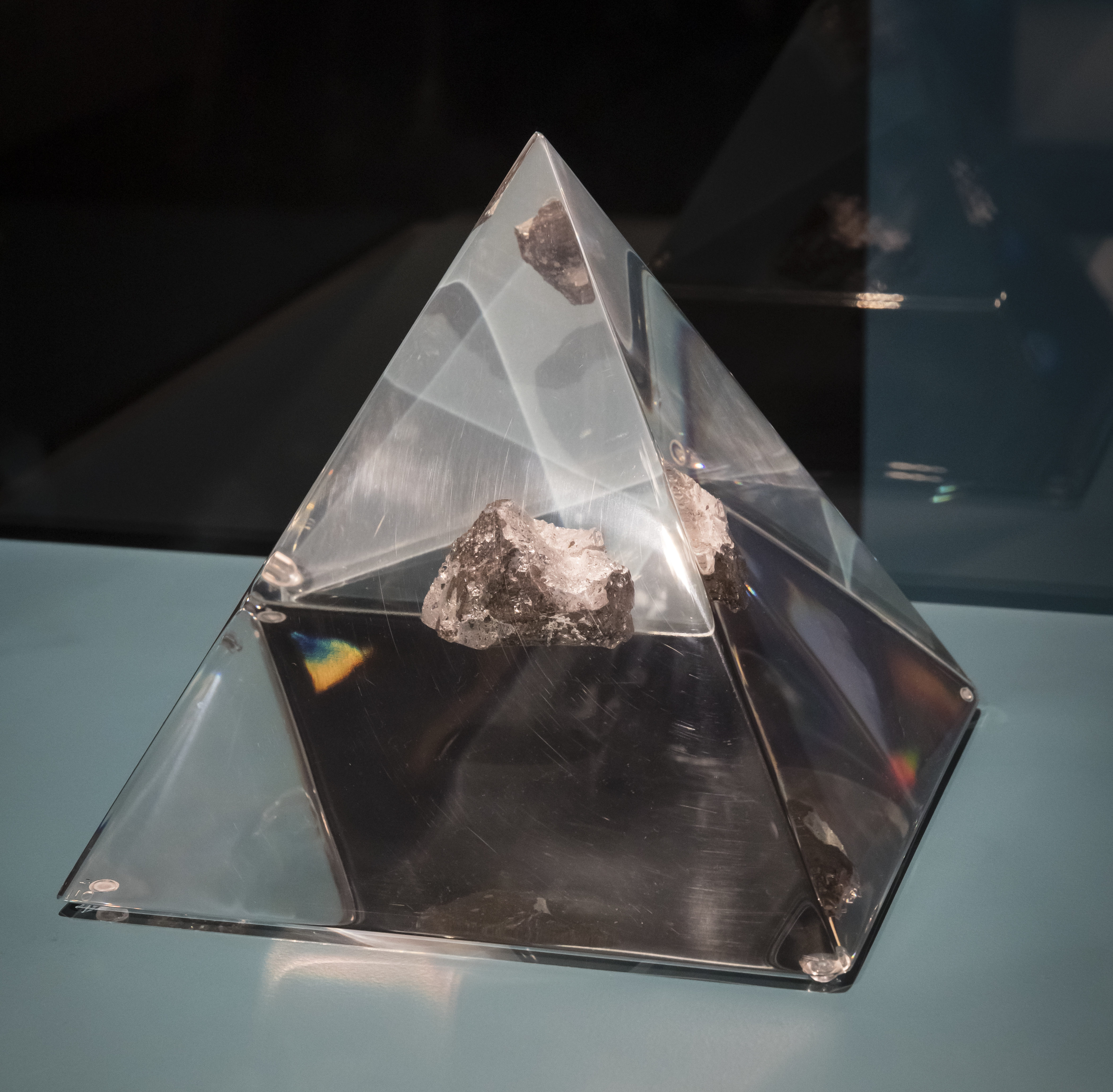

Once on the Moon, the astronauts had a range of scientific goals to accomplish. One of the highlights of the exhibition is a genuine piece of Moon Rock, on loan to the Museum from NASA. Apollo 11 collected 22 kg of Moon Rock samples, which they returned to Earth for scientific analysis, to help understand the Moon’s landscape and origins. This particular lunar sample weighs in at 89g and was collected by Apollo 16 astronaut Charles Duke. It’s been dated at 4 billion years old, which makes it older than most of the rocks on Earth.

Australian Connection

Many people will be unaware that Australia played a critical role in the Apollo 11 mission. Radio dishes around the country, supported NASA as tracking stations, receiving radio transmissions, tracking the spacecraft on its journey to and from the Moon, and most importantly receiving the live TV images of the first Moonwalk.

When Neil stepped onto the porch and began to descend the ladder, two stations were simultaneously receiving the feed – the Goldstone Station in California, and Honeysuckle Creek outside of Canberra – with NASA switching between them trying to get the best picture. Meanwhile, the 64m Parkes telescope in NSW was tipped over towards the horizon, waiting in position for the Moon to rise high enough to see. When Parkes finally received a signal 8 minutes into the Moonwalk, the bigger dish gave such superior quality that NASA stayed with them for the remainder of the 2.5-hour broadcast.

The Moonwalk was watched by more than 600 million people around the world – the largest live TV audience of the time. On display in the exhibition is the ‘Apollo feed horn’ which sat atop the Parkes telescope, and guided the radio waves that carried the TV signals into the telescope’s detector, making this unusual-looking piece of hardware an integral part of the Apollo 11 mission.

Moon Mania

Part of what makes the Moon Landing so special is the impact that it had on people around the world. It’s difficult to think of a scientific event before or since that has affected people in the way Apollo did. The Race to the Moon sparked a decade of Space Age design and popular culture, with fashion, homewares, architecture, music and television all taking inspiration from the early spaceflights and the space technology of the era. The exhibition features classics like the ‘globe chair’, ‘gogo boots’ and more, which took their form from rocket ships, flying saucers and space suits.

Meanwhile, around the world millions of pieces of memorabilia were created and collected as people sought to feel involved in the mission and remember where they were when it all happened. On display in the exhibition are more than 100 pieces of memorabilia from the Museum’s collection, most of which are on display for the first time in Apollo 11. This memorabilia helps capture to how invested people were in the race to the Moon and the imprint the mission left on the public.

Next Giant Leap

The final section of the exhibition reflects on where we are 50 years on from the Moon Landing. Humans haven’t been back to the Moon since 1972, with Apollo 17. Space exploration has continued however, with the exploration of the planets by rovers and satellites, and the establishment of the International Space Station, which has been continuously inhabited since 2000.

The last few years have seen many exciting developments in space, with new technologies changing the way we explore space. The advent of private space companies is now driving what many are referring to as the new space race. With it comes a renewed interest in human space travel: while there is talk of going back to the Moon, the focus is now firmly on Mars, with hopes of establishing a human colony on the red planet in coming decades.

Australia also has an increasing role in space, with the establishment of the Australian Space Agency in 2018, and the launch of Australia’s first payload to the International Space Station and three miniature CubeSats in 2016. The exhibition features three short interviews with space experts that explore these developments: Prof Iver Cairns, project lead for Australia’s INSPIRE-2 CubeSat mission, Anthony Murfett, Deputy Head of the Australian Space Agency, and Dr Carol Oliver, lecturer in astrobiology at UNSW, on the prospect of putting humans on Mars in the near future.

Other highlights of the exhibition include the incredible 7m Museum of the Moon sculpture, created by UK artist Luke Jerram, and a new virtual reality (VR) experience that allows visitors to step inside the Columbia Command Module that carried the astronauts to the Moon and back, both of which I’ll be discussing in future blog posts. In curating this exhibition, I’ve tried to create something that will be enjoyed by all – whether you were there at the time and remember seeing those grainy images coming through the TV – or you’re a budding-astronaut with space travel in your future.

Apollo 11 is open now at the Powerhouse Museum and is included with General Admission.