The Museum has a wonderful collection of busts in the areas of science, fashion and art. From the slightly disconcerting 19th century French paper-mache anatomical models used to explore and demonstrate the workings of the human body to the fabulously formed torso of Chesty Bonds advertising Bonds singlets. Most prolific in the collection are the portrait busts; the smallest is a tie pin made from marble and gilt to commemorate the Italian poet Dante.

Researching the collection made me curious about the origins of the word bust and its history as a sculptural form – it goes back to the grave. Busts were used in Roman and Greek graves, to commemorate the death of a loved one just as portrait paintings have been used to memorialise. The use of sculpted busts is probably from the Etruscan custom of keeping the ashes of the dead in an urn shaped like the person.

From the 1690s the word bust was used as a noun, which meant ‘sculpture of upper torso and head’. This came from the French buste (16c.) and from the Italian busto meaning ‘upper body’ and also from the Latin bustum meaning ‘funeral monument, tomb.’ *

In the past sculptured busts were often life-size, were privately commissioned, and were displayed on private property. The classical bust is rounded at the bottom, hollowed out at the back, and set up on a base. It could form part of a tomb or stand in a niche in a family’s house along with ancestral portraits. Busts depict people living or dead who merit recognition.

Portraiture busts are familiar to us from botanic gardens and art galleries. On display are the heads of long dead Romans, Kings, Queens and emperors. In Australia they are most likely to be marble or bronze reminders of our politicians, explorers and sporting figures.

The Museum’s bust collection has grown over the last 130 years. Amongst the Australians represented are Charles Ulm, Ernest Wunderlich and Sir Henry Parkes. There is a metal bust of Jack Lang in the form of a money box, which seems appropriate given his reputation for dealing with finances.

In the collection is a white marble Queen Victoria bust and three large bronze Russian cosmonauts busts all on display in the Icons: From the MAAS Collection exhibition.

The Queen Victoria bust was believed to have been commissioned by architect Horbury Hunt and was part of the facade of the Farmers department store building in Sydney’s Pitt St. The bust was on site between 1874 and 1901.

There were hundreds of sculpted portraits of Queen Victoria created to adorn public spaces and buildings across Australian colonies in the second part of the 19th century. Most were imported copies of famous British statues and busts but some were made locally. **

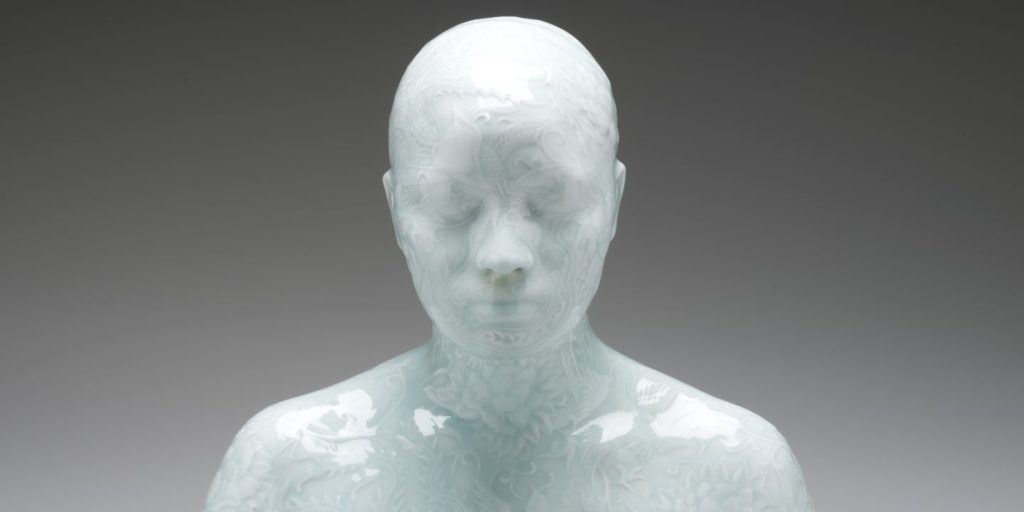

Contemporary artists like Ah Xian have appropriated and adapted the bust form. He is renowned for his delicate porcelain creations. Ah Xian has long been interested in the representation of the figure and the exploration of issues that relate to contemporary society. He has taken a western form, the bust, and combined it with traditional Chinese material and process.

This bust is from the from a series of 40 busts in porcelain. For Ah Xian, the works are a medium on which to project traditional motifs, such as dragons, bamboo plants, lotus flowers and lily pads. They also enable him to experiment with Chinese artistic techniques. Titled Bust 39, this example features a phoenix and peony design, carved in low-relief and finished with a yingqing (shadowy blue) glaze. It is cast from a girl from Jingdezhen whom Ah Xian met while making the series. ***

What’s in a bust?

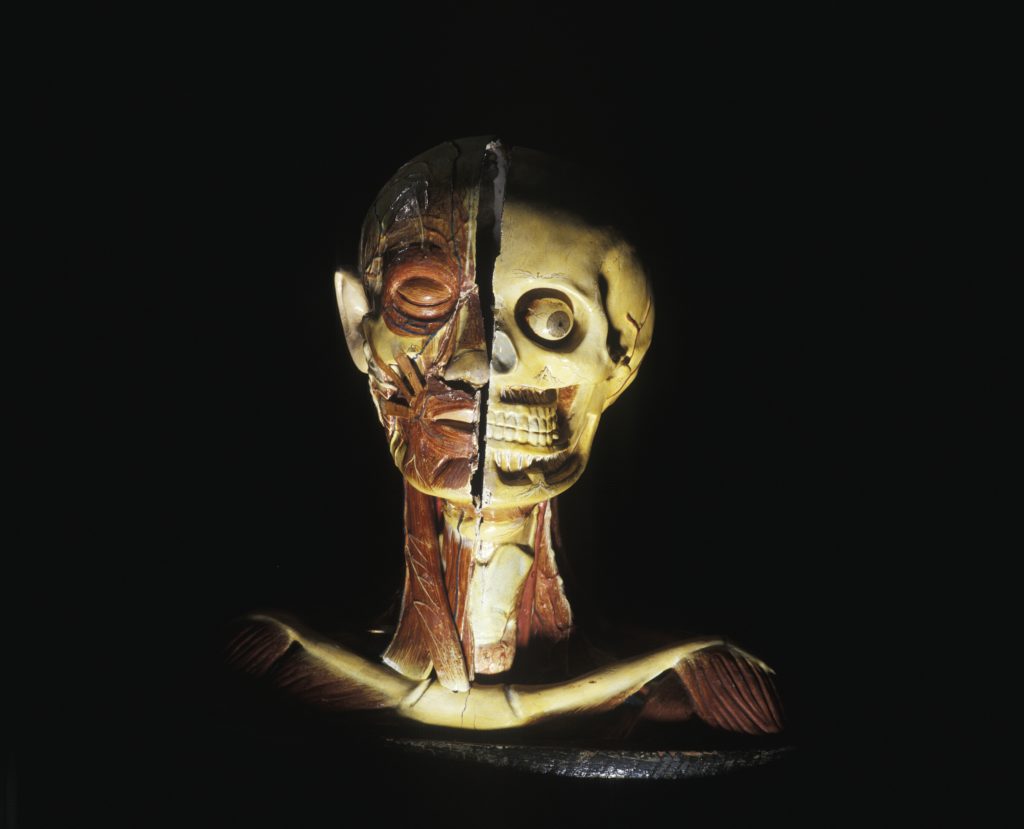

A bust can be made of many materials – marble, plastic, Bakelite, basalt, porcelain, wax, terracotta and even flesh. The anatomical model above contains wood, paper-mache, plaster and paint. The model shows a bisected head. One side shows the muscles, veins and nerves with a closed eye and skin covered ear, while the other side shows the skeletal structure including eyeball and teeth, with roots and nerves. This object comes from a collection of anatomical teaching models transferred from the Sydney Technical College in 1894.

In the early 1800s medical and scientific teaching expanded and there was an increase in demand for anatomical models. Wax, which had previously been used to make models, was replaced by other materials which were less delicate and susceptible to changes in temperature.

The Museum’s collection also contains mannequin busts or torso’s used in selling fashion. Mannequins have fascinated me since visiting many museums and seeing the wild and wide assortment of mannequins and how they are used. Mannequins in the museum are featured in an earlier blog.

Creating copies of busts in the collection with 3D technology will allow a different kind of Museum access and experience. Full appreciation often comes from picking up an item in your hand, turning it around, feeling the material and shape.

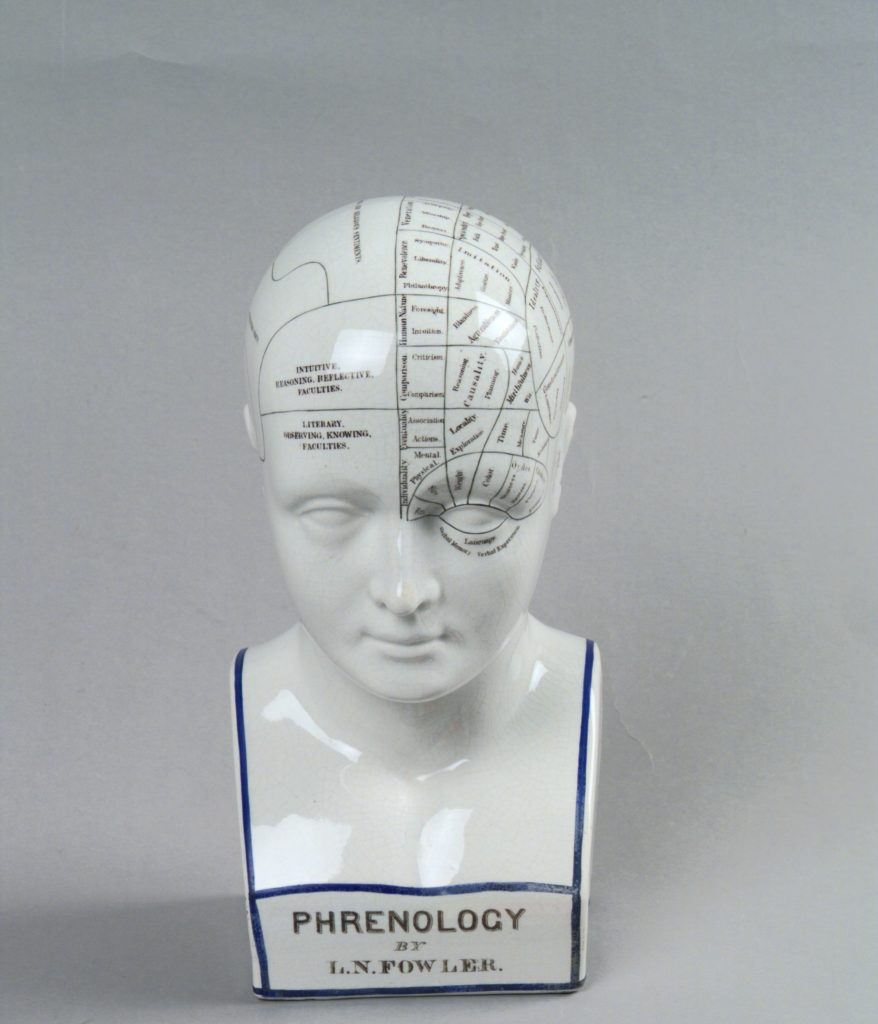

A favourite bust of mine is the phrenology or phrenological bust. Phrenology was a pseudo-science which claimed personality could be derived based on feeling the bumps on our skull. This bust was made in the 1850s by Lorenzo Fowler, a leading exponent. He exploited gaps in the understanding of the brain’s functions at a time when scientists were debating if certain functions occur in fixed brain regions.

See how many busts appear to you in your daily walks.

Written by Anni Turnbull

January 2019

References

*

Online Etymology Dictionary, Accessed 21/1/2019

**

Bust of Queen Victoria, MAAS

Collection 90/960, Eva Czernis-Ryl, Curator

***

Bust 39, porcelain bust by Ah Xian, MAAS

Collection 2008/35/1, Min Kim Jung, Curator

The Art Quarterly Vol XXXIII, No. 3, 1970