The Inside the Collection blog is normally devoted to bringing our readers stories about objects from the Museum’s unique collection, and our latest exhibitions, and the amazing staff who make it all happen. But with National Science Week and the Sydney Science Festival starting this week I’m taking the opportunity to do something a bit different.

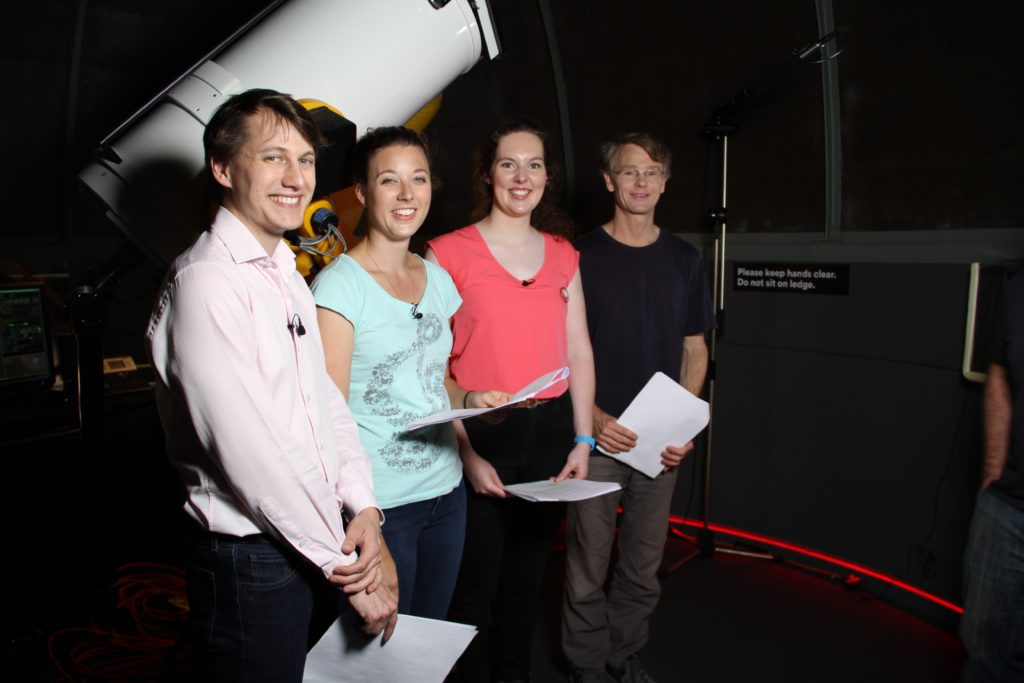

As a science curator, I’m often asked to speak at STEM careers and Women in STEM events – events devoted to promoting the opportunities of a career in science, and encouraging more young women to pursue careers in the sciences. As I’ve attended these events (along with many of my fellow curators) I’ve noticed a lot of common themes in both the stories told by the other scientists speaking, and the questions asked of us by the students.

It’s fantastic that events like these exist now (I don’t remember going to anything like this when I was trying to make career choices), but it got me thinking that there was still a real need for more advice about studying and embarking on a career in science (or any career for that matter). So, in this blog post, I’ve compiled a list of the questions I’m most frequently asked, and attempted to answer them. It should be said that this advice is simply based on my experience and that of some of my colleagues: I don’t pretend that these are the answers!

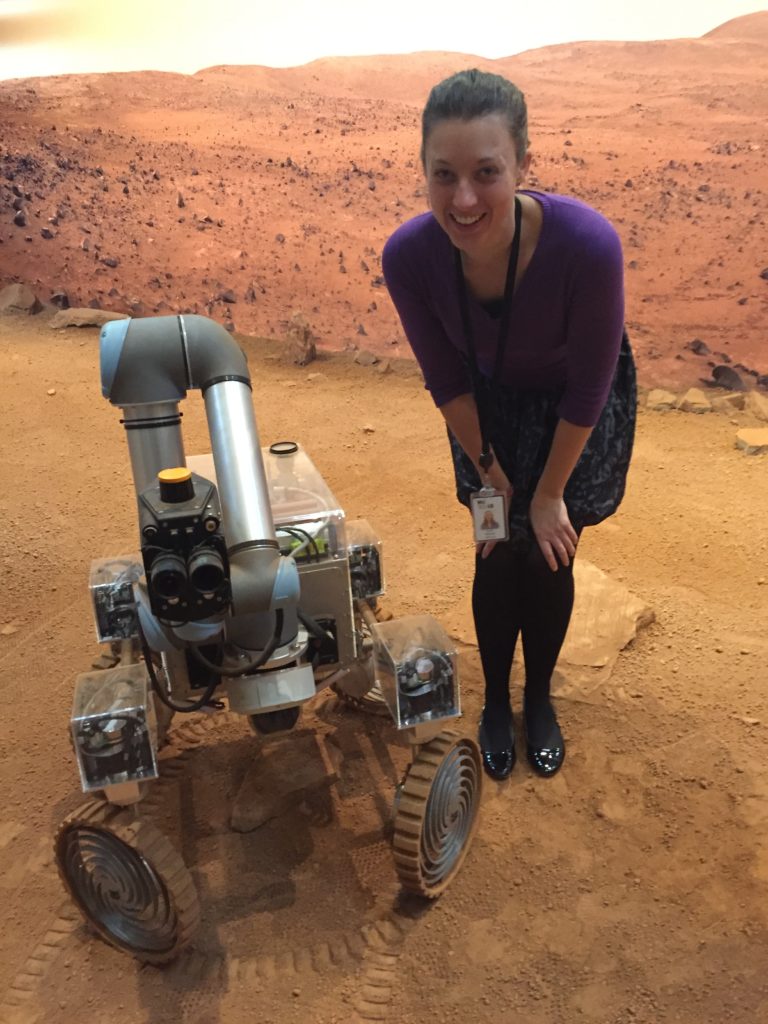

How does a scientist end up working in a Museum?

I always loved science in school, so I took Physics, Chemistry and Biology for my HSC, which was

pretty unusual. I completed a four-year Bachelor of Science (with Honours) at the University of

Sydney, majoring in Physics and Chem. My Honours year research project was in astronomy, which I

absolutely loved, and that convinced me to undertake a PhD in astronomy after my degree. While I

was studying, I also worked as an astronomy guide at

Sydney Observatory

(part of the

Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences). By about mid-way through my PhD I had realised that I enjoyed talking about science more

than I liked doing science itself, and decided to pursue a career in science communication when

I finished. I completed my thesis in 2016, and saw a science curator role (Assistant Curator)

with MAAS advertised around the same time. I applied, got the job, and have been happily working

here ever since.

What does your work entail day to day?

I normally say that the work of a curator is divided into two main areas: developing and

delivering exhibitions; and developing the Museum’s collection. The collection is at the heart

of what we do as a Museum, and an important part of my job is seeking out new objects to add to

the collection, which document the latest scientific discoveries and cutting-edge research, as

well as reflecting on where we’ve come from. In addition to acquiring new objects, I research

and document existing objects in the collection, and write about them online. As a public

institution our collection should be accessible to everyone, and we achieve this (in part)

through our

Online Collection

and

Blog.

Exhibitions are of course the other main way of sharing our collection with the public, and

through them we provide an opportunity for visitors to challenge their ideas or consider

everyday objects in a new light. For me, being a science curator is about communicating science

through the Museum’s collection and exhibitions.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

Every day at the Museum is different and interesting. It’s a cliché, but it’s true. From one day

to another, I can be working on topics as diverse as renewable energy, genetic engineering,

quantum computing, AI, space science and much more. Being part of the Museum of Applied Arts and

Sciences, I’ve even occasionally been called on to work on fashion and arts projects. I’ve

worked on so many amazing projects, but my favourites would have to be

Experimentations, which is a science gallery for children and the first exhibition I

ever worked on, and acquiring the

Cuberider payload

(Australia’s first ever payload to the International Space Station). Right now, I’m working on

an exhibition for next year to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon

Landing, which is obviously right up my alley.

I don’t know what I want to do for a career. How do I choose my HSC subjects?

Pick the subjects you enjoy. It might feel like you’re the only one who doesn’t know what they

want to do, but this is something I’ve heard again and again. I had no idea what I wanted to do

after Uni and, in my experience, people who know what they want to do from a young age (and

actually end up doing it) are the rare exceptions, not the rule. My best advice would be to

continue with the subjects you like and are good at. Some people ask me if they should pick

their subjects strategically based on which will give them the highest ATAR or scale best. In my

mind, that’s a terrible idea: taking a subject you hate will always be a chore; if you enjoy

what you’re studying you’re far more likely to work hard and see that reflected in your marks.

The same advice applies when trying to choose a degree. It doesn’t matter if you know exactly

where you want to end up – study something you enjoy will open up loads of opportunities and no

doubt lead somewhere interesting

How important are my marks? What happens if I don’t get the ATAR I need for my

course?

No one will ever ask about your ATAR again after you start Uni. Of course, good marks will help

you get into the course of your choice, and will give you the best possible start in your

degree. But if you don’t get the marks you need, there are always other ways: you can transfer

degrees after a semester or two (often retaining credit points for some of the subjects you’ve

already completed), or you can take the subject you’re interested in as part of a broader

degree. For example, I had several friends who wanted to study Psychology, but who didn’t get

the very high marks required to enrol in a Bachelor of Psychology. Instead, they enrolled in a

Bachelor of Science or Arts, majoring in Psych. The subjects they took were exactly the same as

those in the dedicated Psych degree, and doing it this way has never held them back in their

careers.

Do I need to be good at maths to have a career in science?

It depends. Some fields of science, like Chemistry and Biology and Medicine, require limited

Mathematical proficiency. Others, like Physics, require very high-level Maths, and it is

therefore a prerequisite for the course and a compulsory part of the degree. For example, with

my Physics major, I had to continue Maths through the first two years of my degree – and I found

it very challenging, I won’t lie. So, if Maths is really not your thing, I’d recommend

investigating areas of science that don’t have such a strong mathematical underpinning. But

regardless, I would always suggest completing at least HSC level Maths, if at all possible, if

you’re interested in a scientific career.

Do I need a degree or postgraduate qualification?

It would be rare to go into a career in science without at least a Bachelors degree. However,

employers are often willing to consider related qualifications if you can show how they are

applicable to the role. For example, before I embarked on my PhD, I nearly took a job with the

Bureau of Meteorology. I’d never studied meteorology or climate science before, but they were

impressed by my Physics and Chemistry qualifications, provided on-the-job training and were

convinced that I would be able to pick up what I didn’t know quickly. As to whether you need a

postgrad degree, that will depend greatly on what kind of career you want to pursue. For

research and academic careers it’s a must, but for many other science-related careers it’s not

necessarily required. Some employers will look more favourably upon candidates with a Masters or

PhD, and it’s often true that that a postgrad qualification will allow you to start out at a

higher level than you would otherwise (in salary and seniority). There are other employers

though who will value job experience the same or higher than additional academic qualifications.

What made you pursue a career in science and do scientists make lots of money?

I definitely didn’t get into science for the money, and I can’t imagine many scientists did; if

you want to earn lots of money, go into finance or advertising. Science is really a field people

gravitate to because they’re passionate about it, and/or are curious to help understand the

world through science, and that was definitely the case for me. Having said that, a science

degree is a very well-respected qualification and will serve you well in the earnings

department. Science graduates typically earn very

competitive starting salaries

when they enter the workforce, have relatively

high salaries

compared to workers in many other careers, and have

lower unemployment rates

throughout their lifetime. If you choose to undertake a postgraduate degree, be prepared that

that might put a dent in your finances for a few years though, while you’re studying.

I’m interested in a career in science but don’t know where to start. How can I find out

more?

One of the best ways you can investigate a science career is to do some volunteer work or

complete an internship. These kinds of programs mean you can spend a short amount of time

(normally a few weeks or months) with several different organisations to gain some hands-on

experience in different fields, and to get a sense of whether it’s something you enjoy and would

be interested in pursuing further. It also gives you the opportunity to make important contacts

in different industries and to ask questions about what their work is like. Here at the Museum,

we offer both

school work experience

and

tertiary internships.

Is a career in science stressful and how do you maintain a healthy work-life balance?

It can be, but I think it depends a lot on you and on the workplace. The world of academia and

science research (which I experienced while doing my PhD) was very competitive. Being surrounded

by a lot of very, very smart people, and knowing that there weren’t enough jobs for all of us

when we finished was fairly tough. I also found that the long timescales and the unrestricted

nature of the research challenging, and ultimately it wasn’t the right fit for me. Other people

love it though. In my current role at the Museum, the work is very different. I’m often working

to very short deadlines and have many projects on the go at once. The people here work

incredibly hard, but I’ve found the work culture to be much healthier overall. For me, whatever

job I’m in, having other interests is critical, and this is something I wish I’d realised in

high school. I love long-distance running (I’m training for the City to Surf right now) and have

always found exercise to be a great stress release. I also have a fantastic group of friends who

I’m forever going to brunch with (but please no one try and tell me this is why I can’t afford a

house yet.).

Science is typically a very male-dominated field. Have you ever experienced sexism in your

career as a scientist?

Throughout my degree and PhD the split of males and females was actually pretty even and I’m

fortunate to never have experienced direct sexism. It is well-documented though that people

(both men and women) exhibit

unconscious biases

towards women and this is something we all need to be aware of. There are also still a lot of

obstacles affecting women who choose to take time off to have a family when they re-entre the

workforce. Luckily, organisations are aware of these problems and are doing more and more to

ensure that women are recognised equally for their achievements, receive the same pay as men,

and have the same opportunities for advancement and promotion. I think having positive role

models to aspire to is incredibly important in encouraging women into science careers – I had

four amazing female supervisors throughout my Honours and PhD years who really inspired me, and

that’s part of the reason that I love speaking at Women in Science events.

What else should I know? What other advice do you have?

Learn to code. If there’s one piece of advice I wish I’d got but didn’t, this is it. Modern

science is an incredible data heavy field, whether it’s astronomy, particle physics or genetics.

As such, much of the actual work of ‘doing science’ involves writing computer software to

process, analyse and understand the data. Even if you don’t go into a research career, or end up

using programming directly in your work, the skills of logic and problem solving that you

develop by learning to code are incredibly valuable. And with products like

Raspberry Pi,

Arduino and the Museum’s

own

ThinkerShield,

learning to code is easier and more fun than ever (wearable technology anyone?).

Beyond that, as I hope my responses here have shown, careers and opportunities in science are incredibly wide-ranging and diverse. This post gives just one perspective. If you are thinking about a career in science, the best thing you can do right now is to start speaking to lots of people and asking lots of questions about possible career avenues to help inform your decision.

Written by Sarah Reeves, Assistant Curator, July 2018